“IT has been an extraordinary journey,” said Alford Gardner, once a 21-year-old former Royal Air Force (RAF) serviceman returning to seek work in Britain and now navigating, in his mid-90s, becoming a crucial living link to an iconic moment in the making of modern Britain.

Gardner is one of the last two passengers alive to have travelled on the Windrush in 1948. So those of us who gathered in Clapham Library were in the presence of living history at the launch of the excellent Windrush: A Voyage Through The Generations photo exhibition in south London, last week. It was attended by many more of those whose family stories have been documented by photographer Jim Grover, and now forms a key part of the social history of Britain.

The Windrush scandal makes the 75th anniversary a bittersweet occasion, as Patrick Vernon of the Windrush 75 network has said, with unmet promises yet to be kept.

The cultural legacies of the anniversary year include Lenny Henry’s important play August in England, compellingly performed by its author at London’s Bush Theatre. Its power comes from the warmth of its story of a life well lived, with family and friends, work and West Bromwich Albion – which makes the disruption and disrespect that drops out of the sky with the Windrush scandal all the more violently jarring.

The play could well become a future classic of the GCSE syllabus. It exemplifies the appetite to ensure that the story of these three-quarter centuries must be one of pride as well as prejudice, recognising both the resilience of the pioneering first generation and the contributions they and their descendants have made to every sphere of British society.

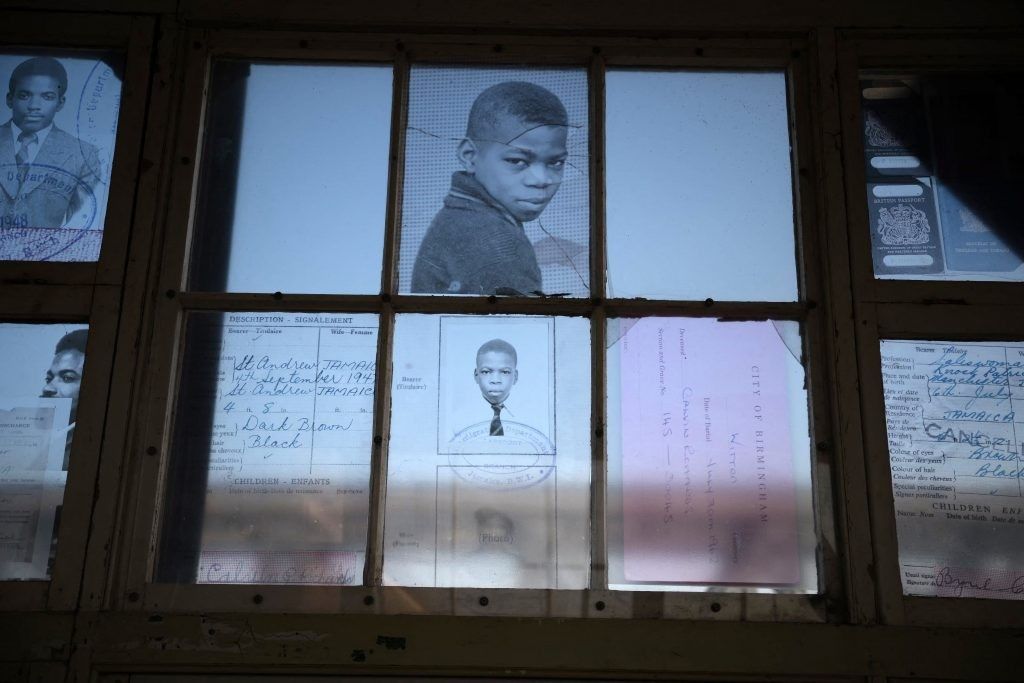

British artist Evewright (Photo by DANIEL LEAL/AFP via Getty Images)

So the 75th anniversary year is stitching the Windrush story ever more closely, perhaps indelibly, into the fabric of British history. Community-led events with Windrush elders in London and Leeds, Birmingham and Cardiff are combined with a stronger recognition of why Windrush matters across sectors of influence and power in British society.

There will be thanksgiving at faith gatherings at cathedrals and by generations of footballers at Wembley, the spiritual home of a sport that would be unrecognisable without the legacies of Windrush.

The NHS has made Windrush 75 a key theme of its own 75th birthday celebrations, recognising that it is no coincidence that these two anniversaries are just a fortnight apart, so inextricably linked have been the modern stories of ethnic minority contribution and our most cherished national institution.

The King, also 75 this year, has reflected by commissioning portraits of the Windrush Generation to hang in Buckingham Palace. The Royal Mint and Royal Mail are issuing special coins and stamps to mark the occasion.

How can this increased symbolic recognition be combined with sustained efforts to deepen the conversation about the past, present and future of modern multi-ethnic Britain? New research for British Future ahead of the 75th anniversary captures the potential to find common ground in the push for greater race equality in this generation. The lived experience of black, Asian and mixed-race Britain is less binary and more nuanced than much of the polarised political and media conversation usually acknowledges. There is both recognition of significant progress over the decades and a strong consensus that this remains an unfinished journey towards fair chances, with much more to do.

There is a striking level of confidence about race in Britain in a comparative context – four out of five ethnic minorities think we are doing better rather than worse than other major democracies – though doing better than post-Trumpian America is to set too low a bar these days.

There is a broadly held frustration that a public conversation about race has become too polarised and divided – with a broad appetite to see less focus on the language of how we talk about race and more on the practical changes that we need to see, from ensuring fair chances in recruitment to tackling online hated.

There is broad public approval across black, Asian and white groups for a mission to set and achieve a ‘net zero’ goal on racism and discrimination in Britain by 2048.

Adopting the Windrush centenary year as a lodestar year for race equality in this country could provide a vision and framework for how every sphere of society, from policy-makers, employers, policing and the judicial system, could play their part. That will mean putting in place now the foundations to secure a generational shift so that race and ethnicity cease to be systemic factors affecting people’s opportunities and outcomes in our society.

This anniversary year is a chance to recognise how Britain has changed for the better over the 75 years since the Windrush. Committing now to an ambitious agenda for change in the generation to come would be the most fitting legacy to complete our national journey towards inclusion and fairness.