HEALTH experts have urged West Midlands residents to get the measles vaccine as cases in the region are spreading in “disproportionately high rates”.

Figures published earlier this month showed 329 of 465 (71 per cent) cases across England from October to February were in the region.

The sharp rise over the past six weeks was mainly driven by cases (80 per cent) in Birmingham, with the majority of patients not being vaccinated.

Across the country, there have been 62 cases in London, and 32 in Yorkshire and the Humber in the same period. The remaining cases were reported in other regions of England.

Of the 465 cases in England, the majority – 66 per cent (306) – were among children under the age of 10, while 25 per cent (115) were in young people and adults over the age of 15.

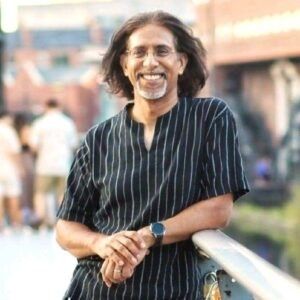

Dr Naveed Syed, health consultant for the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), warned that with Ramadan just weeks away, numbers of measles cases could increase further due to large gatherings during the holy month.

“If you have got an infected person in a room full of people who’ve not had the vaccine, at least 15 out of the 20 will pick up the infection and that’s after a small contact time, 15-20 minutes – it spreads really, really quickly,” said Dr Syed at an emergency briefing, which was hosted last week by the mayor of the West Midlands, Andy Street.

“If people are in a congregational setting, just being cognisant of the fact that Ramadan is coming up and evening prayers, people may be there for an hour plus and if there’s a lot of people who have not been vaccinated, there is a high likelihood that other people will get it because it spreads through coughing and sneezing.”

There were 1,603 suspected cases of measles in England and Wales in 2023, UKHSA statistics showed earlier this year. The figure is up from 735 in 2022, and just 360 the year before.

The UKHSA last month sounded a “national call to action” for more measles jabs for children because of falling vaccination rates and fears a current outbreak could spread.

Dr Syed said nearly 85 per cent of those contracting measles have not had any doses of the combined measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

“That just shows the importance of vaccine,” he said. “If we can vaccinate up to about 90-95 per cent of the population, that would protect everyone else in the community and you’d basically stamp out any measles outbreaks.

“The vaccine is not just for children. We were out in pop-up clinics at the weekend and people were coming in bringing their kids and having it themselves as well, because when they rang their GP for the kids, they realised they are not vaccinated.”

Jenny Harries, head of the UKHSA, previously said some members of the Muslim community were wary of the vaccines because one of the MMR vaccines on offer has a pork-based derivative.

But she said she wanted to let people know that an alternative was available and was “very effective”. Dr Syed said it was important that the public received the relevant information regarding the MMR vaccine. “There are legitimate concerns in some communities around the MMR vaccine and there are a lot of misinformed concerns in the communities,” he said. “There are obviously issues around people getting vaccines, there are cultural issues, certain religious issues, because there are two MMR vaccines, one of them contains pork derivatives, the other one doesn’t. This one can be given to people of Muslim faith and others, such as vegetarians.

“It’s important for us to be culturally aware for those people and get that message out there that there are alternatives to the main one which does have pork gelatine.”

Communication around the cultural issues surrounding the MMR vaccine hasn’t been “consistent”, Jo Tonkin, acting director of public health at Birmingham City Council, admitted.

“We’re doing work to really understand which groups don’t have the MMR vaccine and what are the barriers that people are facing in getting it,” said Tonkin.

“All of the evidence points to things like health literacy and access. When I talk about health literacy, I’m talking about understanding basic information about what vaccines and immunisations are and translating that into action (getting more people vaccinated). Doing something with that information and also considering it alongside cultural and faith beliefs.”

She added: “We need trusted voices in the community to work with us to encourage our population to get their MMR vaccines that includes community leaders, that includes faith leaders. What we need to do is to listen and understand the barriers that your communities are facing in the community and respond to them.

“All of the directors of public health, their teams, our integrated care boards, our education colleagues, are all out there talking to communities and faith leaders.” Feedback pointed to people not realising how serious measles is because “we don’t see it anymore”, Dr Syed said.

Measles usually starts with cold-like symptoms, followed by a rash a few days later. Some people may also get small spots in their mouth, according to the NHS. The measles infection can spread very rapidly and lead to serious complications, lifelong disability and even death. It can affect the lungs and brain and cause pneumonia, meningitis, blindness and seizures.

The NHS says the best way to protect against measles is through vaccination.

The UK had previously achieved “measles elimination status”, Harries said, but lost this in 2018 following an increase measles cases in the country and vaccine levels lower than the 95 per cent.

Currently, the average number of children starting school who had both doses of the MMR vaccine stands at 85 per cent. Vaccination rates across the country have been dropping, but there are particular concerns about some areas, including parts of London.

The lowest rates nationally were seen in the capital, with one area – Hackney in the east – with only 56.3 per cent of children vaccinated, according to the latest health service figures.

Dr Mubasshir Ajaz, head of health and communities at the West Midland Combined Authority (WMCA), acknowledged that people had become more wary of vaccines due to the Covid-19 pandemic and felt it was important to find ways to dispel fears around the MMR vaccine.

“It’s okay to point people towards the NHS website which has a whole leaflet on both vaccines as to what the ingredients are. “Everybody kind of became a semi-expert on vaccines when Covid came up. Even if those buzzwords that people have heard in the news, if we can clarify those points and the fact that we’re not hiding any kind of ingredients either, it’s really useful for parents and community members.