LUCY FULFORD, a 34-year-old freelance journalist and filmmaker, has written a personal book, The Exiled: Empire, Immigration and the Ugandan Asian Exodus, about the Asian expulsions from Uganda.

What is different about her account is how she has woven her own story and that of her family into the larger history of what happened in Uganda, both before and after 1972, when some 30,000 Asians arrived in the UK as refugees.

Fulford is a 2020 alumni of Penguin WriteNow, a publishing scheme aimed at finding promising voices from under-represented communities. Her book is dedicated “to adventurers and everyone searching for home”.

When she was a little girl, Fulford found it difficult to answer the question, “Where are you from?” But now, she is happy her background takes in India, Uganda, Britain and Australia.

“When I was younger, I maybe struggled, wanting a bit more of a singular identity to latch on to,” she admitted during a conversation with Eastern Eye. “But, now, I think it’s great to have pieces of you from different places. And I’m loving finding out more about them.”

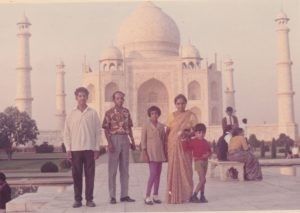

Her maternal grandparents, Mathukutty and Kunjamma Mathen – they preferred to be called “Philip” and “Rachel” – were Christians born near Thiruvananthapuram (formerly Trivandrum), the capital of Kerala in south India. Shortly after their wedding on January 1, 1953, in the Anglican church in Kottayam, they were recruited by an Englishman who had come over from Uganda. Both were teachers, so they were needed in Uganda, especially Philip, who taught mathematics and science.

They set sail from Bombay [now Mumbai] for Mombasa later that year – Rachel didn’t let on she was pregnant. They took the train through Kenya to begin a new life in Kampala, where their first child, Fulford’s mother, Betty, was born in January 1954. They had another daughter and a son. Had it not been for dictator Idi Amin’s expulsions, they probably would have remained in Uganda.

In 1972, as they packed their bags, the man who bought the family Peugeot also took possession of their sheepdog, Jack. They wept when a couple of German women took away their beloved Alsatian, Simba. Their cat was shot by a neighbour. Parting from pets has always proved another painful part of the immigrant experience. A family friend had to say goodbye to Sheru, a “handsome” lion hand-reared from the time he was a cub.

Betty had been sent to a girls’ boarding school, Tormead, in Guildford in Surrey. However, during the expulsions, her parents and two siblings didn’t have to go to a camp. “It was just a luck of the draw” that they quickly found an empty house in Cambridge through church connections.

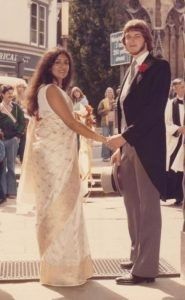

And it is in Cambridge that Betty met Martin Fulford, an Englishman from Surrey who was reading computer sciences as an undergraduate at Peterhouse. They married in 1978 at the Roundhouse Church, a well-known Cambridge landmark. Fulford’s grandparents found teaching jobs in Cambridge, but “downgraded” from the senior posts they had held in Kampala, where Rachel had become a headmistress.

But the English weather did not suit Philip and Rachel. As a cure for his bronchitis and other chest ailments, they decided to make yet another move with their two younger children – this time, across the world to Australia. They were joined a few years later by Betty and Martin.

It was in Sydney that Fulford was born in January 1989. She had a happy childhood in Australia, but when she was 12, her parents returned to Cambridge. After attending a local secondary school, she moved to Bristol to read history.

Fulford writes: “It was in Bristol, a widely multicultural city, where I was first called a ‘Paki’.”

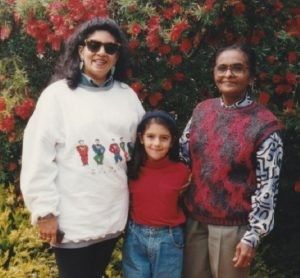

She retains idyllic memories of Australia: “You can’t hear it in my voice anymore, but I had an accent. I was fully Australian and never really thought about anything else. I had a great childhood living in the Sydney suburbs. We weren’t by the sea, but we spent a lot of time at the beach, also getting out into the bush hiking. It was a nice outdoorsy upbringing. I love Australia. I miss it a lot.”

Her grandparents, who fired her imagination with tales about Uganda, passed away in Australia over a decade ago.

Fulford said: “My middle name is Rachel. So, I have had that with me.”

She also lost her father about 10 years ago when she was 24. Her mother is settled in Cambridge.

All the twists and turns in her life explain why for Fulford, there isn’t a simple answer to the question: “Where are from you? No, no, where are you really from?”

She has certainly been brave and adventurous. At 19, she went on her first trip to Uganda. That was only for a week, because she was also travelling to Zimbabwe and South Africa. But the last leg of the trip to India during her gap year had to be called off because she broke her ankle skydiving in South Africa.

To gather material for her book, she spent a month in Uganda last year, visiting Kampala, Jinja and Iganga. She hired a car and drove around with photographs from the family album, so she could compare Uganda past and present.

In her book, Fulford has also bent over backwards to understand why Amin, who was initially welcomed after he overthrew Milton Obote, got away so easily with expelling Uganda’s entire Asian population within 90 days. She acknowledges his behaviour was irrational and brutal, but she also thinks the structure the British imperialists had put in place – the white man at the top, the Indians in the middle, and the Africans trapped at the bottom – planted the seeds of future trouble.

“I don’t feel any negativity around the expulsion,” she said. “When you look at how the Ugandan Asian story has been told, it has often had this slightly victim narrative. And that’s understandable, because people did lose everything.

“But I think it is important to look at maybe why it happened, and how black Ugandans felt at the time. And that viewpoint hasn’t always been given enough airtime. There was a lot of inequity in society. When I look at Uganda now, I think it’s great that a Ugandan family lives in my grandparents’ old house.

“Amin fed into things like this by making declarations that he had a dream that this is what he needed to do. But he himself had spoken about this (expelling the Asians) prior to the dream. Obote had also been talking about a move to remove south Asians. There’s a precedent for it. It’s not coming out of nowhere. And then when you look at the reasons given by Amin, which is, ‘south Asians are milking the economy and focused on financial drain and not investing,’ suggesting people were (ab)using Uganda essentially.

“But behind that is this colonial framework, which sets south Asians up to be the kind of successful class and so there are reasons behind it. South Asians were in Uganda because of the British empire. I just wanted to make sure that we looked at Uganda – before and after 1972.”

The Exiled: Empire, Immigration and the Ugandan Asian Exodus by Lucy Fulford (£22), is published by Coronet, an imprint of Hodder & Stoughton, a Hackette UK company