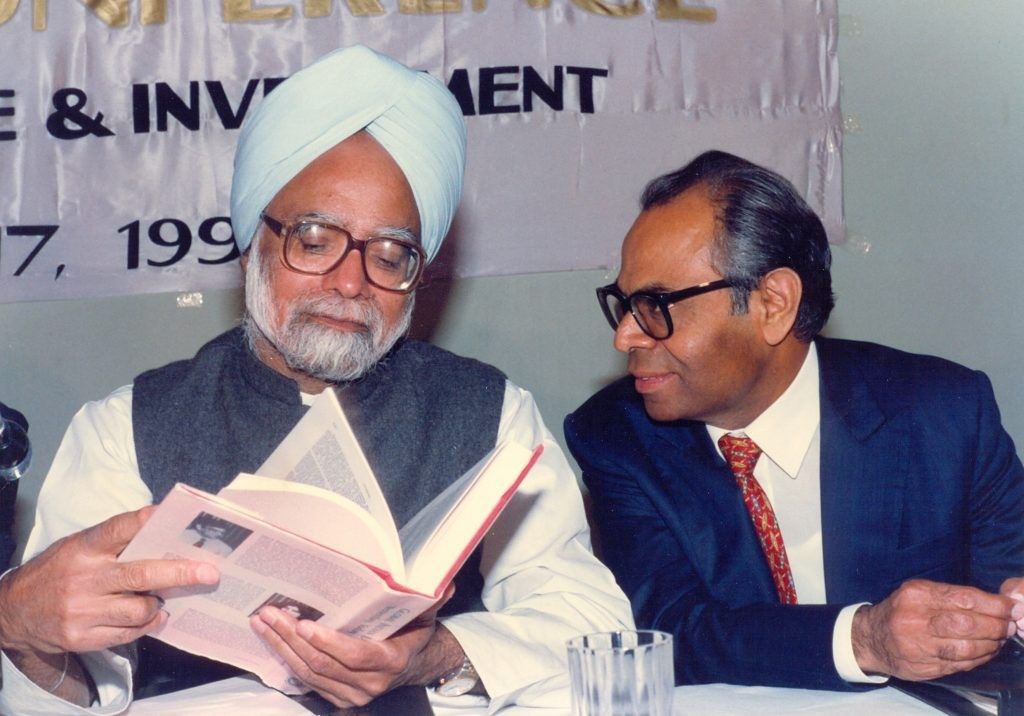

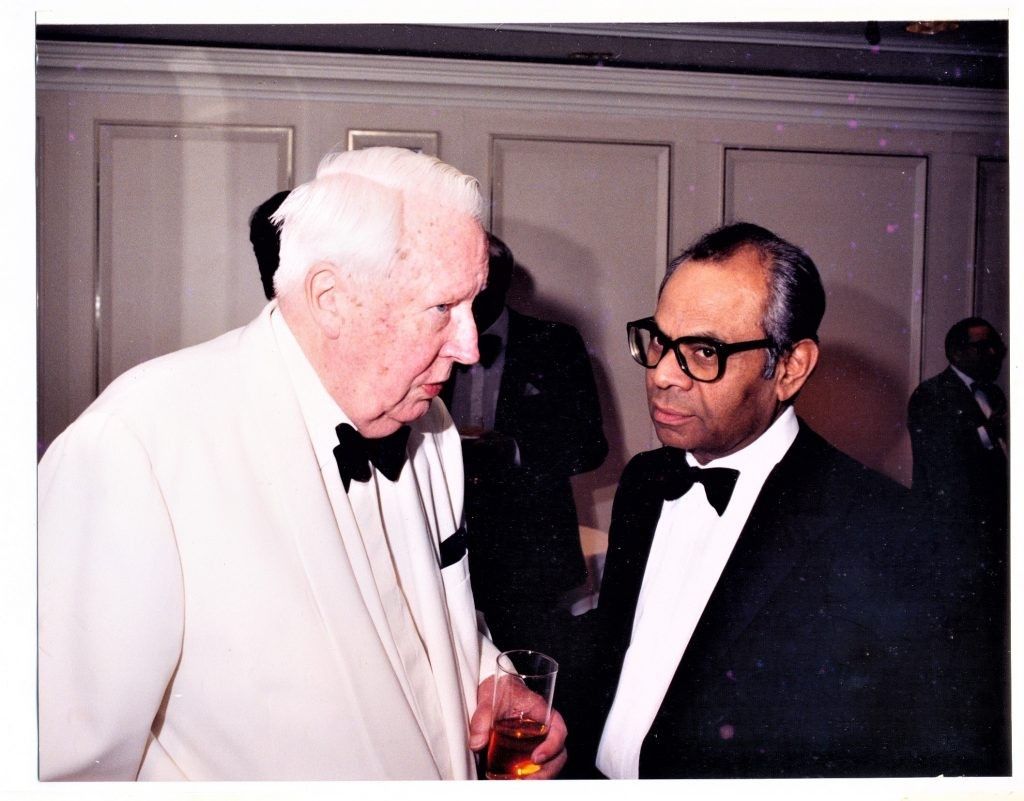

Srichand Hinduja (SP) interacted with many world leaders – among them Sir Edward Heath, Sir John Major, Tony Blair, George HW Bush, Morarji Desai and Indira Gandhi.

Indeed, SP was in the habit of sending briefs with his thoughts to heads of government. Quite often these were on how to improve relations with India. But I found SP’s account of how he and his brothers had got the Shah of Iran out of trouble perhaps the most entertaining.

This, in his own words, was the story SP told me: “In the early 1970s, Iran was faced with a crisis – a shortage of onions. The common man depended on onions for most Iranian dishes. Now the price had shot up from one toman a kilo to 15-16 tomans a kilo – in those days a dollar was worth about seven tomans. There was a big hue and cry among Iranians, ‘Why can’t we get onions?’

“What made it worse was there was also an onion shortage among the usual suppliers, Turkey being one of them. There was a similar shortage of potatoes.

“The Shah of Iran summoned his commerce minister who said weakly, ‘Your Majesty, we can’t get any onions.’ ‘Have you inquired from the Hindujas?’ wondered the Shah. By then, we had a reasonable presence in Iran. The Shah then snapped, ‘Go and place the order with them.’

“The order was for 200,000 tonnes of onions and 200,000 tonnes of potatoes. There was only one catch: they had to be delivered within 14 days. The minister rang Gopi, my younger brother who was then based in Teheran.

“I was in Bombay when Gopi telephoned with the news. My first reaction was shock, since we had never before dealt in either onions or potatoes.

“As luck would have it, India that year had produced bumper crops of both. Since they were perishable, farmers were throwing them out by the heapful.

“I telephoned Gopi to say that there were plenty of potatoes and onions around, but it would be difficult to get the required quantities out through the Indian ports in time because of congestion at our end. There was only one solution – to send them via the land route. But would Pakistan agree?

“The Shah was on cordial terms with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the prime minister of Pakistan. So we suggested that perhaps His Majesty would be kind enough to have a quick word with his good friend, Mr Bhutto. The telephone call was presumably made because 500 spacious air-conditioned trucks were cleared for the journey from Iran through Pakistan to India.

“But Bhutto was also playing a game – for at the last minute, he raised an objection: ‘I don’t want any Indian drivers.’

“There was nothing for it, but to hire a jumbo jet, recruit drivers in South Korea and fly them to the trucks. A couple of days later, the trucks arrived on the Pakistan-India border.

“Then Indian bureaucracy intervened. The customs officer on the border said: ‘You cannot take the trucks into India. You first have to pay a 350 per cent bond guarantee on each truck that they will go back the way they came. You say you are planning to take 500 trucks inside. Who knows when – or if – you will bring them back?’

“To pay import tax of 350 per cent on the value of each truck wasn’t a joke. And there were 500 trucks. The tax payable would easily exceed the value of the consignment we were moving. The idea that I would flog 500 trucks sent by the Shah to customers in India was preposterous.

“I flew to Delhi where I knew the prime minister’s powerful principal secretary, PN Haksar, and even Indira Gandhi herself.

“Haksar, whom I admired greatly, was sympathetic. ‘Look, SP, I’ll try, but my hands are tied. This is our policy on imported vehicles. We could try and amend the policy but that would take time, months, perhaps years.’

“In our London office at that time, we had a manager by the name of Krishna Golikari. I instructed him to telex me a bond paying the 350 per cent tax drawn on the British Bank of the Middle East. After the bond was paid, the trucks were released and arrived in a storm of dust in the Punjab city of Jalandhar.

“We bought what we needed direct from the farmers, paying them up to 50 rupees a quintal (in those days, 13 rupees was worth a pound and 100 kilos made up a quintal). We worked round the clock, buying from places such as Pune and Nasik.

“Some people advised us the Shah was making billions from the sale of oil and that we should sting him for the highest possible figure. We found it easy to reject that suggestion and we kept to the contract. Twelve days after the order, the ‘Hinduja onions and potatoes’ were in the provincial markets of Iran.

“Later we heard that the minister telephoned the Shah and said, ‘You were right, Your Majesty, the Hindujas have performed.’

“The Shah then issued instructions for an ex-gratia payment to be made to us. The minister ran to us waving a fat cheque. ‘His Majesty has given this to you as a little extra,’ he gushed.

“Our response was courteous, but firm, ‘Will you thank His Majesty for his generosity? He should not misunderstand us, but we cannot accept. We have performed our duty.’

“As a result of the onions business, the Shah developed a great deal of confidence in us. But our move was not intended to be a ploy. Getting the onions to him was a challenge and the more difficult it became, the more I was determined to ensure the job was done, especially as we had more or less promised the Shah we would deliver.

“The Iranians also agreed to give oil to India on favourable terms. India received five years credit with a two-year moratorium. It represented a dramatic turnaround in relations. We convinced the Shah it would be better for Iran to have friendly relations with India. We also persuaded the Shah and Mrs Gandhi to exchange small gifts on birthdays. Mrs Gandhi sent mangoes.

“As business developed between Iran and India, in cement, sugar, rails, wagons, steel, textiles, and jute, the Shah felt more confident that he would get the right quality if it was channelled through the Hindujas.

“I think I contributed to improving relations between Iran and India. It is only possible to do that when you don’t ask for favours for yourself which diminishes your status. In one year, I flew 66 times between the two countries.

“Although we had access to the Shah, Mrs Gandhi and other leaders, we have always believed in keeping a distance – ‘retain a distance from the king, from the elements, from the fire and the ocean, because if the regime changes, they can hang you’. This is a basic Vedic principle.”

In London, the Hindujas had an office at 29, Museum Street, opposite the British Museum, since 1962, “but in 1979, we moved our global headquarters to London”. SP had a lot of time for Mrs Thatcher who “understood politics as well as economics. I gave the concept of the Indo-British partnership to her.

“At first, her ministers, including Michael Heseltine and Douglas Hurd, did not take much interest, but later they did, when they realised she was serious.

“At one Diwali function, she deputed John Major – who was then not a senior minister. When she saw my expression of disappointment, she reassured me, ‘Listen, he’s the future prime minister.’”

SP said he persuaded then US president Bill Clinton to change his attitude to India.

“At a time when Bill Clinton was anti-Indian, we got Tony Blair to change his mind by organising a meeting between Blair and Brajesh Mishra, the national security adviser who had come with a brief from [then Indian prime minister] Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

“Clinton was anti-Indian because of India’s refusal to sign the non-nuclear proliferation treaty. I sent Blair a memo outlining how the real rival to the west was not India, but China. Blair then met Clinton who understood what the British prime minister was saying.

“I was with Brajesh Mishra at Downing Street when he met Blair and handed over Vajpayee’s letter. This was subsequently handed over to Clinton by Blair.”

SP also “met Prince Charles at Kensington Palace where he said he wanted to eat the vegetarian food I had taken. Later he became a patron of the Hinduja Cambridge Trust which brings students from India to the university.