THE more things change in Pakistan, the more they remain the same.

At the time of writing, reports from Pakistan indicate Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari is to be his country’s new foreign minister in Shehbaz Sharif’s government.

The 33-year-old is the son of Benazir Bhutto, Pakistan’s first and only woman prime minister who was assassinated in 2007 in Rawalpindi, and Asif Ali Zardari, the country’s former president. After Benazir’s death, Bilawal, although only 19, was named co-chairman of the Pakistan People’s Party, his father being the other. Zardari also hyphenated his son’s surname to Bhutto-Zardari to emphasise the Bhutto legacy.

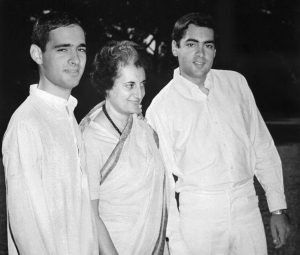

Shimla, while Benazir Bhutto (second from right) looks on

After the tragedy of losing his mother, Bilawal returned to his studies at Christ Church, Oxford, where his grandfather, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (who was hanged by Ziaul Haq), had been an undergraduate in the 1950s.

Bilawal and Pakistan’s ousted prime minister, Imran Khan, have one thing in common – the latter was also at Oxford in the 1970s. Imran was at Keble College, while Benazir was at Lady Margaret Hall and went on to become the first Asian woman president of the Union Debating Society in 1977. Imran and Benazir knew each other, but weren’t friends. When Benazir’s younger brother, Murtaza, challenged her for Pakistan’s leadership, she and her husband had him bumped off (according to Murtaza’s daughter, Fatima Bhutto).

When Bilawal returned to the UK after his mother’s death, he explained being made co-chairman of the PPP by saying “politics is in my blood”. He had to be given special protection at Oxford and went for a while as Bilawal Lawalib – his first name spelt backwards.

In 2010, when president Zardari met the British prime minister, David Cameron, at Chequers, Bilawal and his 16-year-old sister, Asifa, went along for the ride and afterwards posed for a group photograph. Cameron was also an Oxford man, as was Boris Johnson, his contemporary.

Bilawal was last week in London to meet former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, whose younger brother has replaced Imran. Bilawal’s expected appointment as foreign minister is not necessarily good news for India. Unlike Benazir and Imran, who both had friends in India, Bilalwal has been belligerent and bellicose about Pakistan’s neighbour from a young age. At 22, he typically told a party gathering in Multan: “I will take back Kashmir, all of it, and I will not leave behind a single inch of it because, like the other provinces, it belongs to Pakistan.”

To be sure, that was then, and this is now. But like his grandfather and his mother, Bilalwal will consider becoming leader of Pakistan both his destiny and his birthright. Army willing, of course.

India cannot complain too much about dynastic politics since it pretty much invented the practice. But things don’t seem to be working out quite so well for Rahul Gandhi. When Rahul did his MPhil at Trinity College, Cambridge – his (assassinated) father, Rajiv Gandhi, and great grandfather, Jawaharlal Nehru, had been undergraduates at Trinity, too, while his (also assassinated) grandmother, Indira Gandhi, had been at Somerville College, Oxford – he went under the name Rahul “Vinci”, also for security reasons.