OUTSIDE of the UK, there is no country where PG Wodehouse is more popular than India, it has been suggested by Paul Kent, who has just published the final part of a trilogy of books on the great English comic writer.

This is possibly because of the “subversive” element in the writings of Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, often known affectionately by his nickname, “Plum”.

He created many characters of whom the best known – and loved – are Jeeves, who was not a butler, but a “gentleman’s gentleman”, and his employer, Bertram (“Bertie”) Wooster.

Kent has also made a disclosure that many fans of the comic writer will find shocking – which is that at one stage when Wodehouse’s confidence was low, he pondered “whether to kill off Jeeves on the strength of a single bum review in The New Yorker, which opined that the character had ‘frankly … become a bore’. He hadn’t, of course; but certainly from 1947 to 1954, it’s difficult to argue Plum’s muse was firing on all cylinders. As Sophie Ratcliffe politely puts it, this was a period of ‘consolidation rather than intense creativity’ during which his muse was actually all over the place, with self-confidence reducing the flow of his creative juices – though you’d never guess it by looking at his publishing schedule.”

Wodehouse, who was living in France when the Germans invaded, was interned and accused of helping the Nazis by making a number of (innocuous) radio broadcasts from Berlin. He was later cleared by an MI5 inquiry, but some of the mud inevitably stuck.

Kent told Eastern Eye in an exclusive interview: “After the Second World War, Wodehouse understandably had quite a few crises of creative confidence, and I think he really did have crippling doubts about the viability of his created world, of which Jeeves was the figurehead. This went on for quite a while, but really, to start again from scratch with a whole new created world wasn’t a realistic proposition and, thank goodness, he didn’t!”

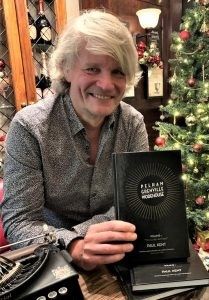

Of his three books on Wodehouse, Kent brought out This is jolly old Fame in 2019; followed by the second volume, Mid-Season Form in late 2020; and most recently, volume three The Happiness of the World.

Kent explained: “The thing to stress about the trilogy is that it is not a biography – it’s a tour of Wodehouse’s comic imagination – how and why he wrote what he wrote – with bits of biography thrown in to place the argument in context. It’s not chronological either, dotting around Plum’s 100-book output and 75-year career as necessary.”

He added: “Volume one tries to give some idea of the range and depth of his work, and to introduce the central argument that Wodehouse deserves to be considered not just as a great comic writer, but a great writer, period, who can stand shoulder to shoulder with any of the ‘serious’ literary greats. It also explores how his mature voice developed between 1900 and 1920 and investigates his lyric writing (for the stage) in some detail.

“Volume two looks at his ‘mid-season form’, his triumphant creation of Jeeves and Wooster, Blandings, Ukridge and the rest. In particular, it focuses on the evolution of the Wodehouse formula, his plot structures and character types.

“Volume three examines the relationship between Wodehouse World, time and history, and how his work is surviving and thriving, despite being so completely identified with the early 20th century. The final chapter looks at how Wodehouse, although so quintessentially English, has proved popular all over the planet. All the way through the books, I try to put Wodehouse’s output in a literary context, investigating his sources and influences.”

Wodehouse has indeed been published all over the world, in translation if necessary.

“But it’s India where Wodehouse seems most closely interwoven with the nation’s consciousness, his popularity not just undimmed but seemingly growing,” Kent has asserted in volume three.

“Reports tell of the availability of his work on station platforms and airport bookstalls alongside the latest bestsellers, and down the years a number of writers in the UK, US and India itself have been prompted to speculate as to why this should be.”

Kent noted that in the December 2005 issue of Wooster Sauce, the quarterly magazine of the PG Wodehouse Society in the UK, “it was announced that Right Ho, Jeeves had been translated into Hebrew”.

In the same issue, “Sushmita Sen Gupta wrote a considered piece detailing how the internet, then a mere infant, had already helped bring India’s scattered but sizeable Wodehouse community together. Numerous sites continue to thrive, and so I decided to commission my own survey from the ‘Fans of PG Wodehouse’ Facebook group, which at the time of writing has 15,000 or so members and is the largest of several to be found on that platform.”

Kent added: “Many commentors seem to have been alerted to the existence of Wodehouse by their parents or word of mouth, and, as Vikas Sonak points out, this has ensured that a love of Wodehouse has been passed down several generations.

“Others have noted that because English is widely spoken and formally taught in India (figures vary wildly, but it’s conservatively estimated that around 10 per cent of the population – that’s 125 million people – regularly speak it), Plum’s work has ‘invariably’ found its way onto exam papers as examples of some of the finest prose ever written. Moreover, Wodehouse titles can often be found in local libraries, or those run by the British Council or the local British Consulate. Many of my correspondents have carried over that love of Wodehouse from formative years into adulthood, praising its restorative qualities and the way it chimes with the Indian sense of humour and love of wordplay.

“I apologise to those who responded to my request for not being able to name them all individually, but from the dozens of replies, Karan Kapoor’s stood out for his thoughtful exploration of Plum’s ‘strangely subversive appeal’.

“It’s clear that the Indian ‘take’ on Wodehouse is complex, and is rather more than purely escapist or nostalgic, somehow chiming at a deeper – and perhaps more disruptive – level than we might credit.”

In volume three, Kent has also included “an unapologetically lengthy extract from a speech (Shashi) Tharoor gave at the 2008 Wodehouse Society dinner in London, which for me brilliantly sums up how Wodehouse World can be of this world and yet not of this world at one and the same time – while none of us remain any the wiser as to why that might be.”

Tharoor had said: “Wodehouse is one British writer whom Indian nationalists could admire without fear of political incorrectness. My former mother-in-law, the daughter of a prominent Indian nationalist politician, remembers introducing Britain’s last Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, to the works of Wodehouse in 1947; it was typical that the symbol of the British Empire had not read the ‘quintessentially English’ Wodehouse but that the Indian freedom fighter had.”

Asked by Eastern Eye what he made of Wodehouse’s devoted following in India, Kent responded: “I think it’s fantastic – and utterly unique. Of course, there’s more than one way to appreciate Wodehouse, but Indian fans seem to take such joy in the language and absurdity of the plots that they maybe immerse themselves in his created world more joyfully and completely than many others. In the impromptu survey of Indian readers I conducted for Volume 3, the word that cropped up more often than any other was ‘subversive’. Which is exactly right – Wodehouse’s humour is very subversive, so much so that many readers don’t even notice it. But Indian readers seem to, and absolutely revel in it.”

Kent isn’t quite done with Wodehouse: “There’s going to be a volume four (tentatively titled Wodehouse at the Theatre), and until that’s ready, I’m publishing at least ten essay-length pamphlets focusing on single topics. The first one, PGW on…Food is already out, and the rest will follow at two-monthly intervals. Titles include Sport, Money, Hollywood, Cats and Dogs, Love and Family.”