EASTERN EYE readers who want to discover how British artists have depicted colonialism and slavery over the centuries should visit the Royal Academy’s (RA) latest exhibition.

Entangled Pasts 1768-Now: Art, Colonialism and Change is the RA’s “brave” response to the Black Lives Matter movement and the toppling of slave trader Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol in 2020.

Armada (2017-2019).

The academy is showing the works of 34 great masters from the past. British Asians will perhaps take note of Johann Zoffany’s 1768 work, Colonel Blair with his Family and an Indian Ayah (1786); The Ghauts at Benares by William Hodges (1787); Edward Penny’s painting (1772-3) of Lord Clive receiving from the Nawab of Bengal a grant for Lord Clive’s Fund for the relief of distressed soldiers and their dependents; Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray by David Martin (1779); and Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley (1778).

There are plenty of black figures in paintings from the past – but often on the edges as anonymous servants. When it comes to Indians, the art works are much more complex, but the empire is usually portrayed in a positive way as a force for good.

With Zoffany’s painting of Blair’s family, a note says: “The painting depicts the family of Colonel Blair, an East India company officer. On the right, Blair’s youngest daughter strokes a cat, held by an unnamed figure. The present title of the painting suggests that she is an Indian ayah (nanny) but, given her childlike appearance, it is possible that she was the daughter of an ayah who looked after the Blair children or an illegitimate child of Blair.”

There is also a poem by Imtiaz Dharker questioning whether Blair’s is entirely a happy family.

The Royal Academy also invited 25 contemporary artists – among them Bharti Parmar, Lubaina Himid, Mohini Chandra and the Singh Twins – to come up with their invariably critical responses to the masters from the past.

The academy points out: “Past works of empire in India are in conversation with works by contemporary artists of south Asian heritage including Shahzia Sikander, Mohini Chandra and the Singh Twins.”

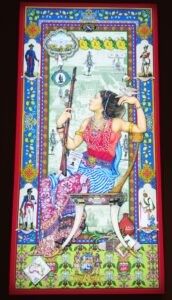

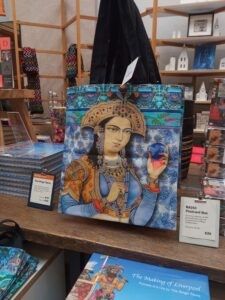

The Singh Twins, Amrita and Rabindra, have offered their 2018 illuminated painting: Indiennes: The Extended Triangle from the Slaves of Fashion series. It is perhaps the ultimate recognition of their fame that branded merchandise from the Singh Twins, such as bags, is on sale in the RA shop (along with blank sheets of drawing paper from Bharti Parmar). Sikander’s 2020 work, Promiscuous Intimacies, is included. Migration is represented by Hew Locke’s major installation Armada, (2017-2019).

The exhibition poster is Kara Walker’s No World, from an Unpeopled Land in Unchartered Waters (2010).

Entering the Royal Academy’s Annenberg Courtyard from Piccadilly, visitors are confronted by Bahamian Tavares Strachan’s dramatic gold and black sculpture, The First Supper (2021-23).

At the exhibition preview, Axel Rüger, the RA’s secretary and CEO, told journalists: “The exhibition does take its origins from the foundation of the Royal Academy in 1768. We use that as our point of departure to reflect on its history.

“And while the exhibition is tied to the history of the RA, at the same time, it is looking outward at people and places. It’s attempting to shed light on the complex entanglements and contradictions of British art in the context of British history. The exhibition takes at its core artistic dialogues between historic works from the past, and works by major contemporary artists, many of whom are actually members of the Royal Academy.”

The RA said: “The exhibition was programmed in 2021 in response to the urgent public debates about the relationship between artistic representation and imperial histories. These debates were prompted by the Black Lives Matter protests and the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol in 2020.”

It added: “Entangled Pasts is presented across the RA’s Main Galleries, organised into three thematic sections that intertwine narratives across time. Sites of Power examines absence and presence in Grand Manner portraiture and history painting, reflecting on the decades surrounding the foundation of the RA, which saw both the height of Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade and the emergence of the movement for abolition, as well as new networks of artistic patronage associated with the East India Company.

“Beauty and Difference traces the proliferation of aesthetic norms via drawings, prints, poetry, sculpture and photography in works that embody the moral contradictions of the Victorian age, during which abolition became a fashionable theme for artists while Britain continued aggressive colonial expansion.

“Crossing Waters takes an international perspective on the widespread legacies of the Middle Passage, including its far-reaching ecological consequences, through immersive spaces that offer time to reflect on our common history, its ramifications, and parallel issues today.”

The exhibition’s lead curator is Dorothy Price, professor of modern and contemporary art and critical race art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, which she joined in September 2021 from the University of Bristol.

She recalled that the exhibition was first discussed with the Royal Academy “after the murder of George Floyd, the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, plus the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston from its plinth in Bristol. I was based in Bristol at that time and had seen this first hand. These are important contexts for the decision for the Royal Academy to take this really brave move.”

Price added: “My first response was how can you possibly make an exhibition about such an enormous traumatic history, a history that began back in the 16th century, and the whose legacies are still being felt in different ways today. How can we talk about this that doesn’t just seem a bit navel gazing?

“What’s very apparent about the Royal Academy is its role as a training ground for artists who then go off into the empire, work for the East India Company, work for other traders and patrons. It’s very quickly apparent how global the RA is in relation to these traumatic histories.”

Two colleagues whom she invited to join her in putting together the exhibition were Dr Esther Chadwick, lecturer in art history at the Courtauld Institute, and Dr Cora Gilroy-Ware, an expert on 19th century art at St Peter’s College, Oxford.

Price said: “I developed a set of curatorial principles to guide us. Wherever possible, I wanted to ensure that we foregrounded black and brown sensitivities in these narratives. We could not replicate the traumas that these histories evoke, but also not whitewash them either.”

Price told Eastern Eye the role of the British artist over the centuries was to show the empire was benign, and black and brown people were generally happy to live under enlightened colonial rule. “Absolutely, that it was about this creation of a vision of the empire, that it was a happy place, a place of harmony and a place of dignity,” she responded.

On Zoffany’s painting of Blair’s family, she said: “Zoffany painted that in India. Although it’s recreating an English drawing room theme, you’ll see intimations that it’s not in England – the foliage, the screens at the back. What the Blair family have done is they’ve tried to take their England into India, and Zoffany then paints them as English people, but they’re in India.

“They call the girl an Indian ayah, although that’s in doubt. She is slightly shorter than the child at the end, she’s with the pet, possibly a playmate for the child. All the figures of the Blair family have shoes until you get to the Indian girl at the end – who is barefoot, so she is put in a lower position. The idea of her being an ayah is an unusual one because she’s a child herself. It’s a complex painting.”

She spoke of the contemporary artists in the exhibition: “These are artists, like myself, who grew up as children in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, when there was no space for people of colour within a British identity.

“We are seeing the change in British culture post Windrush. We were kept apart and separate, whereas now it’s beginning to be more integrated. Contemporary academicians (at the RA) have been working for decades with these issues. What does it mean to be British if you’re a person of colour?”

Entangled Pasts 1768-Now: Art, Colonialism and Change is at the Royal Academy until April 28.