“WHEREVER you may live in the United Kingdom, and whatever may be your background or beliefs, I shall endeavour to serve you with loyalty, respect and love”. A hereditary monarch does not need to run for office, unlike the candidates standing in England’s local elections last week. Yet his constitutional role depends on sustained public consent. As Pete Tong set those sampled words of King Charles III to his Ibiza Classic Feel the Love, the Windsor Coronation concert made clear that there is a King’s manifesto for this reign.

The Coronation ceremony itself involved a delicate coalition pact to bridge a thousand years of Christian tradition and the multi-faith presence in modern Britain. In the sacred and sublime setting of Westminster Abbey, the essentially Christian character of the ceremony remained unchanged.

The Oath itself, set in a statute of 1688, reflects the history of anti-Catholic discrimination, yet the Catholic Archbishop of Westminster could this time offer a public blessing to the King. Just how unlikely this would have been for the last three centuries went largely unremarked in our more secular age. Archaic Royal rituals of state – presenting the King with his spurs of courage, his sword of justice, and his glove of mercy – were seized as opportunities to diversify modern participation.

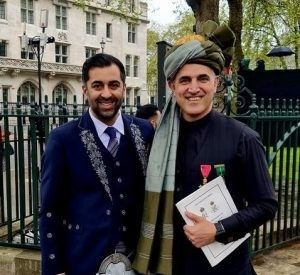

If the offer was of presence and participation, rather than equality, many attendees found the message of inclusion moving. Sabir Zazai felt privileged to attend a Coronation that he felt captured Britain “as a country of many colours, flavours and traditions”. Granted sanctuary in Britain as a refugee two decades ago, after a dangerous journey in the back of a lorry, he contributed to that blend in his traditional Afghan outfit and turban, looking resplendent pictured alongside Scottish First Minister Humza Yousaf in tartan. Yet that ethos of welcome and hospitality in the Abbey contrasts sharply with the political climate he must navigate as he now leads the Scottish Refugee Council’s challenge to a government bill seeking to rule almost all claims for asylum inadmissible in Britain. “We cannot be welcoming on the one hand and cruel on the other,” he told me.

After the local elections, Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer received conflicting advice as to whether to reinforce or bridge post-Brexit Britain’s social divides. King Charles III, with more time to think long-term, has made a clear choice to reach beyond the monarchy’s core support to those not already onside, especially the young.

So the Windsor concert, unlike previous Royal pop concerts, had a clear narrative. That hypothetical Royal campaign pledge-card might boil down to five key priorities: public and voluntary service; environmental sustainability; championing British culture, traditional and modern; confidence in the Commonwealth; with inclusion and diversity at home too now becoming perhaps the King’s signature theme.

Charles III is the oldest and best prepared Monarch in British history. His reign will be shorter than his half-century apprenticeship. This may prove a lower profile era for the Monarchy. Over twenty million – a third of us – saw his Coronation crowning moment live on television. That is still unusually large – since almost infinite choice has fragmented audiences – but only two-thirds of those who saw the Queen’s funeral, or England football’s penalty shoot-out heartache against Italy in Euro 2020.

This Coronation year followed two weddings, two jubilees and a state funeral in the previous decade. No Royal event of similar scale is likely within the first decade of this reign. The King’s test will be less the monarchy’s mass reach and more its sustained effort to find new relationships to broaden its coalition of support.

I was at the Windsor concert with my ten-year-old daughter. It was a joyous occasion. Stevie Winwood’s “Higher Love” sung with choirs from across the Commonwealth, whose flags including those of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh were projected onto Windsor Castle alongside the red, white and blue of the Union Jack, had the whole place jumping.

Patriotism can take many forms – angry or hopeful, exclusive or inclusive – as my new book How to be a Patriot explores. What struck me most in Windsor was the contrast between an often-polarised politics of identity and how the soft inclusive power of a modern British cultural patriotism – of pride in place, of literature and language, from high to pop culture – might yet transcend some of the social and political divides.

Symbolism matters, up to a point. It can provide a vision of a society we would like to imagine ourselves to be, if we can do the spadework too. “If the inclusivity of this concert was a genuine representation of our country, I would be very proud to live here”, one twitter respondent with mixed views of the monarchy told me. The prospects of the King’s message of inclusion may depend on how far those seeking to govern join the chorus too – or strike a more discordant note.