IT was a speech that showed how much words can matter.

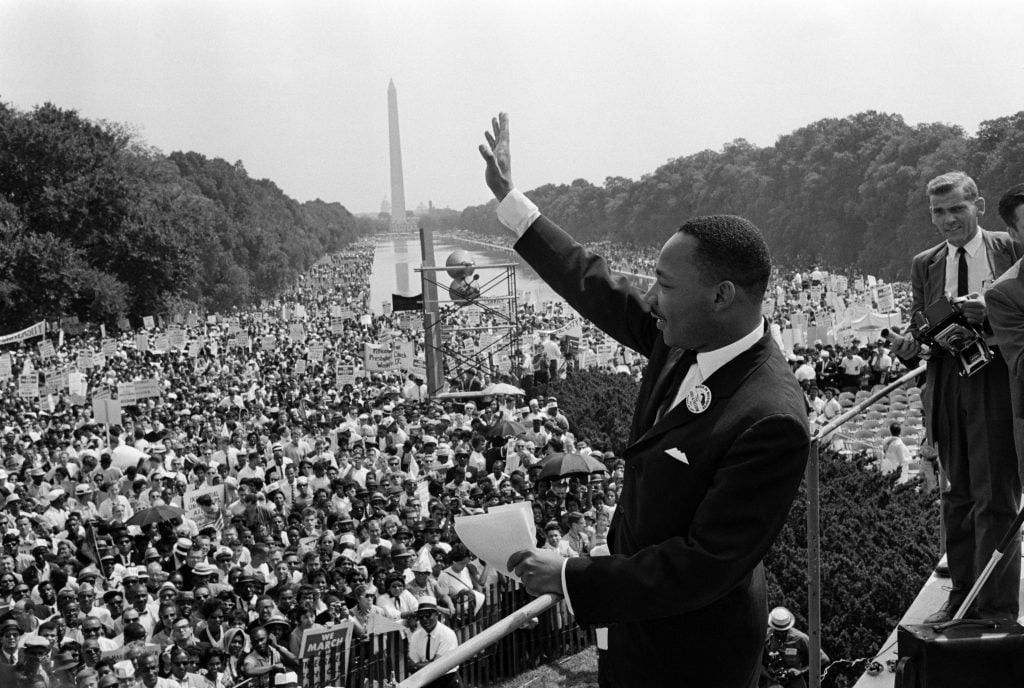

America has been marking the sixtieth anniversary this week of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech, delivered to the quarter of a million people who had marched on Washington in 1963 to demand civil rights.

The moment helped to make King a posthumous secular saint, more warmly remembered than any President. Thousands of streets across America bear his name. That can give us a sanitised image of a man who was much more polarising in his own era, a time of great fear in America. The civil rights movement had seen peaceful protest met with violence – from police brutality, officially sanctioned by state governors to defend segregation, to waves of bombings and shootings.

President Kennedy wanted the March on Washington postponed, though he spoke in support once it proceeded. Malcolm X was emerging as a radical alternative for those frustrated by King’s commitment to turning the other cheek.

Kennedy, his brother Robert, Malcolm X and King himself were all to be slain by the bullets of assassins within five years.

In such turbulent times, the success of the March on Washington was to convey hope in America. About a quarter of the marchers in the August sunshine were white, three-quarters were black. Network television coverage emphasised this multi-ethnic nature –– giving many people their first glimpse of how a more integrated America could be an ideal shared across racial lines.

The patriotism of King’s speech is among its most striking features. He declares that his dream is “deeply rooted in the American dream.” If the promise of America had been denied to Black Americans, King chose not to denounce the country’s rhetoric of freedom and equality as a myth but instead to demand that its promise should be redeemed in full.

Six decades on, that remains a work in progress. Thousands marched on Washington this weekend to ‘continue the dream’. Race in America has continued to lurch between progress and backlash as the eras of Obama and Trump have again shown. Less than a third of Black Americans say the US has made a fair amount of progress on race across these six decades, with white Americans twice as likely to think so. New Pew research finds that the question of whether urgent change is needed, or if the push for equality has already gone too far, polarises America down party and ethnic lines as sharply today as it did in the 1960s.

The US civil rights movement inspired many outside America. In the UK, the Bristol bus boycott of 1963 overturned a colour bar on bus conductors. Northern Irish Catholics modelled their civil rights marches on it – in the part of the UK where social discrimination had the strongest institutional and political support.

Yet Britain’s landmark speech on race was not a visionary dream but a dystopian nightmare. Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech – just a fortnight after Martin Luther King’s April 1968 assassination – declared it essential to halt the emerging reality of a multi-ethnic Britain to avoid “recreating in the Britain’s green and pleasant land, the haunting tragedy of the United States,” as he objected to the Race Relations Act removing the freedom of businesses and landlords to racially discriminate.

Can words still change our world? Great social causes remain, from social inequalities to climate change, but few faith or civic leaders could emulate the reach of the movement that King built. Today’s more complex challenges on race and inclusion can lack the brutal moral clarity of racial segregation.

It is much easier to nominate great political speeches from the 20th century than the 21st. Technological shifts fragment audiences and shorten our attention span. This is a decade when the British public have been asked to make existential choices – over Brexit and Scotland’s place in the UK – but slogans and soundbites took priority over major speeches about what was at stake.

In politics, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown placed more emphasis on speeches to make a public argument than their more recent successors. Speeches still matter as a test of political performance, helping David Cameron sweep to the party leadership, albeit as much on style as substance. Boris Johnson was a talented wordsmith as a columnist and comic but lacked the attention span to fashion his thoughts into serious speeches – or to focus on the work of his Government.

Maybe ours has become a post-speech age. Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer head this Autumn into a pre-election year, each armed with a five-point plan about their priorities and missions for government. Neither has yet attempted a major statement of their political philosophy or vision of the future. They may have accurately read the mood of an age more sceptical about dreams – but there may again be prizes one day for those able to make politics inspiring again.