How much is immigration mainly a question of numbers?

Record levels of net migration certainly create a political headache for the Prime Minister. The figure was just over half a million, when the statistics were last published six months ago.

This week’s statistics, published on Thursday, will be higher still. They report figures for the 12 months up to September 2022.

The Prime Minister can point out that the new record numbers reflect what the Sunak administration has inherited from Boris Johnson and (briefly) Liz Truss. But Sunak, as Chancellor, was a co-owner of those policies, while the government’s legitimacy to govern depends on the 2019 manifesto, in which it proposed that overall numbers would come down.

The politics of immigration is often about numbers. Yet the post-Brexit immigration debate about “taking back control” shows how immigration policy is about more than numbers too.

The rising immigration numbers since 2019 result from the choices that the Government made about what to do about immigration. Sometimes, those policy choices were responses to unexpected crises. Refugees from Ukraine and the BN(O) visa for Hong Kongers will together add around a quarter of a million to the 2022 figure.

These were popular decisions, with the Government under pressure on Ukraine to act more quickly to let refugees in.

But the Government made many other decisions to increase immigration that were not crisis driven. These reflected Boris Johnson’s belief in the control, choice and contribution case for immigration – a view shared by his Chancellor, Sunak.

After EU free movement, the Government set a target to increase the number of international students, reintroduced the right to work for overseas graduates, removed the caps on non-EU skilled migration, and dramatically increased the number of people recruited from overseas for the NHS and social care to help mitigate staff shortages in the sector.

The home secretary, Suella Braverman, is vocal about the need to cut the numbers. Significant reductions would mean reversing almost all of those policies, rather than tinkering around the edges of the international students policy, changing whether one-year masters students can bring a spouse. The rest of the Cabinet are sceptical about the Home Secretary’s plans.

When the prime minister made five pledges in his New Year speech, he made four careful, gradual incremental promises he hopes to keep – and a much more memorable one about stopping the boats, that makes absolute promises he cannot keep.

He is now suggesting a sixth unofficial target – to reduce immigration numbers below those he inherited – that is much more achievable. Without 200,000 Ukrainians arriving again in 2023 and 2024, net migration could fall significantly with no policy changes at all.

Reducing net migration down to 2019 levels of a quarter of a million will be much more difficult. Trying to do that quickly would damage his other pledges on the economy and the NHS. Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has gained from the Office of Budget Responsibility revising growth upwards and showing an improved fiscal position because the immigration numbers are higher than the Government promised.

But immigration is also about more than control and contribution; it is about who we are. An account of the gains of immigration for the NHS and for universities, or for the economy more generally, is ultimately a ‘they are good for us’ argument. That may invert the ‘they take our jobs’ case but this is still a story of ‘them and us’.

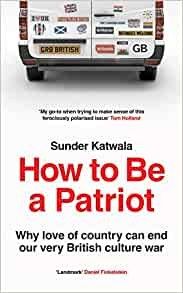

My new book How to be a patriot argues that what really secures sustained consent for migration depends on answering a deeper question about identity and integration – how do people become us?

Half a century ago, Enoch Powell projected that by the end of the century, four million of “them” – the ethnic minorities – would mean the death of the nation.

Much of that argument in 1968 was about numbers: whether Powell had got his numbers right or wrong. His calculations were, in fact, close to what the census would show by the end of the century.

What Powell was wrong about was less his numbers than their consequences. His deep pessimism reflected his belief that it was all but impossible, with a handful of exceptions, for migrants or their children and grandchildren – like me, or Rishi Sunak – to ever fully identify with this society, or be fully accepted into it.

“Too many” has been a constant theme of the immigration debate in every generation. Attitudes towards numbers are softer than ever before, despite record levels.

Securing consent for immigration depends on handling the pressures of change on public services and housing better. We should pay more attention, too, to what happens after people get a visa – to social contact, integration and citizenship.

The countries most confident about identity and patriotism in this fast-changing world will be those that put most practical effort into the question of how people become us.