EARLIER this year, George called me.

“Barnie, I need a favour,” he began, “I’m involved with a migration charity, and we’re telling the story of how migrants have helped Britain.

“We want an exhibition in Leicester, use my name, I’ll turn up and do what I need to do, can you help?”

Of course, the answer was yes. It was George, after all, and you don’t say no to him.

I first met George in person on general election night in 2001.

We were both covering the Leicester count, and he was the face of the BBC, and I was some unknown who was making his name covering the riots in the north of England.

“Hello Barnie, I’m George,” he began. I was stunned. The humility that I wouldn’t know who he was.

He was the biggest south Asian star in broadcast journalism.

“I just wanted to say how brilliant you’ve been in covering the riots and teaching me about the communities I come from.”

It was a pinch-me moment, and one I’d never forget. That trademark kindness and diffidence.

Over the years, we’d stay in touch, and when we saw one another in the newsroom, he’d always make time to have a chat, no matter how close it was to 6 pm.

We weren’t close, but even when I left the BBC, George would respond to my texts when I ranted and raved about some perceived slight.

No matter what, George never forgot he was south Asian and that he was a force for good for future generations of journalists – just read the social media posts to know what we thought about him.

I know that’s an odd comment, but that’s because I know of people who want to distance themselves from their communities and heritage.

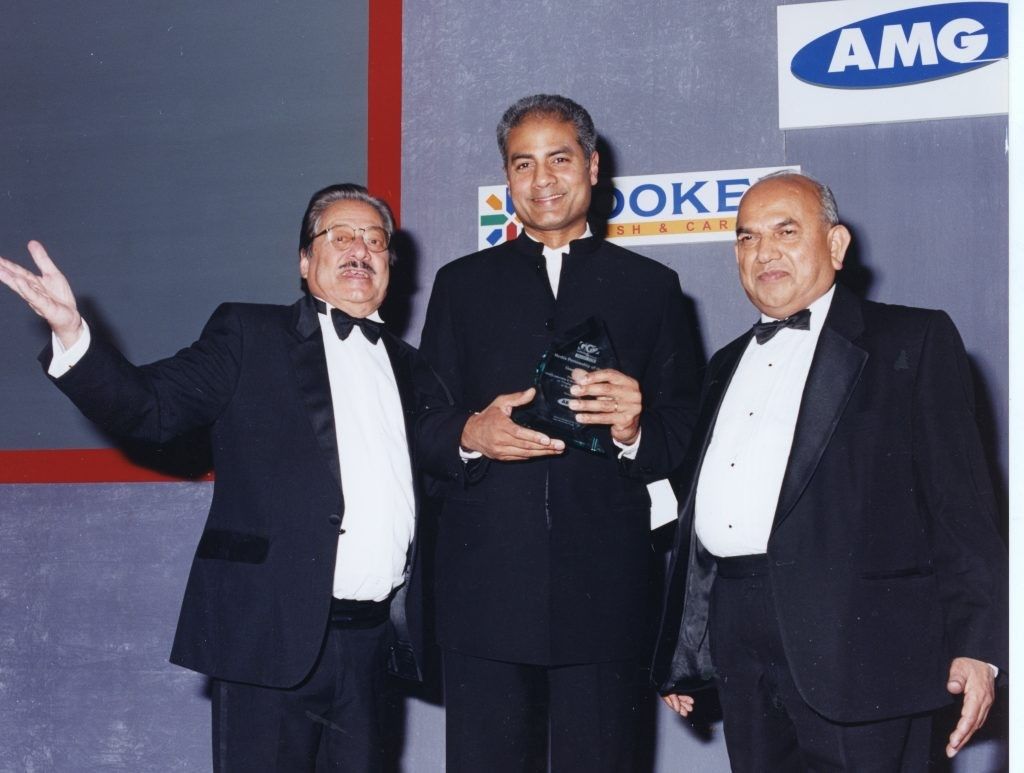

I wrote his profile when he was included in the top 101 most powerful south Asians in the UK for the GG2 Power List, published by the Asian Media Group.

It was Christmas 2021, and George was off work because his cancer had spread.

Before I reprint that article, I wanted to share a final memory.

Something I’ve never shared with anyone except my wife – until now.

The BBC knows that I’ll hold it to account when it comes to racial diversity, or lack of.

Few people of colour say it as it is – that the BBC, for all its claims about being racially diverse, is failing in leadership.

It remains hideously white, and that was my final conversation with George.

This wonderful man revealed that he, along with some of the senior people of colour, had met the director-general to explain why journalists were unhappy about diversity in the corporation.

“You’re right about the leadership, Barnie,” he said. “I don’t see people like us at the highest editorial levels.

“I wish I’d done more, maybe once I get back, I will.”

We’ve lost a true legend today.

Someone whose legacy will be measured by those he inspired.

Here is my tribute to George, the way I’ll remember him.

One of journalism’s most generous souls who always praised other south Asian colleagues

For someone who got news that his cancer had spread, and on top of that he had contracted Covid, George Alagiah is in a relaxed, positive and reflective mood, wrote Barnie Choudhury last year.

For someone who got news that his cancer had spread, and on top of that he had contracted Covid, George Alagiah is in a relaxed, positive and reflective mood. We are speaking via Zoom and he is not in the BBC studio. His granddaughter, whom he clearly adores, is asleep in the next room, and he is thankful for his life.

“I got diagnosed in 2014, I had treatment for 18 months, and I had a couple of years clear,” he recalls. “It came back in 2017. Basically, it had never gone, but what happened this year was a bit of a shock. We’d always restricted it to the bowel, liver, that kind of area. Anyway, what happened this year was that it went to the lungs, which is where it is now, among other places.

“So here I am pootling along, thinking, well, we’ve got it in check. I mean, it’s still there, it still shows up on the scans, but you know, the chemo’s working and it’s not growing. Then suddenly you’re told it’s gone to your lungs, and, in some ways, that was harder to take.”

Apart from being on our screens reading the BBC 1 main news programmes, in 2020 Alagiah was publicly recognised by being shortlisted for the Society of Authors award. His debut novel, The Burning Land, was considered for the Paul Torday category, which recognises a first novel by a writer over 60.

“People say, why did you go into fiction? To me, it wasn’t such a huge leap, actually, because all writing is about looking for the truth. But there are just sometimes limits to the work that you and I do. If you don’t have the facts, if you haven’t got the interview, you can’t tell the story well.

“Fiction allowed me to tell stories about the world I’ve experienced and seen as an eyewitness, but I could never really bring to the screens or to the magazine pages. That’s what took me to writing, in this case, about what some people are calling a new colonialism. The way in which rich countries and rich people are buying precious land in poorer countries.

“It’s a story I tried to do as a report and never quite made it. It’s a very secretive business, and I thought, well, I’ll just make it up and tell the story as fiction. It was hugely satisfying to do, liberating, when you don’t have to list your sources to your editor. To be on some shortlist was brilliant. I’ve got a couple of ideas, some non-fiction, some fiction, but I hope it’s not the end of my fiction writing days.”

So where does his love of journalism and writing come from? Alagiah’s Tamil father was a civil engineer, while his mother looked after the home and her five children. He was the only boy in his family and came to the UK as an 11-year-old from Sri Lanka.

Surprisingly, perhaps, he emigrated to Britain on his own, to a state boarding school in Portsmouth. The newsreader still remains in contact with some of the friends. It was in Durham, where he read politics, where he fell in love with journalism, and the person who was to become his wife.

“I don’t think I was a brilliant student, I really got into the newspaper The Palatinate, which I edited for a time. I loved that, and I just enjoyed the freedom of being there. The other thing about Durham is that it was the first time I really became aware of class. I don’t know what it’s like now, but it was a strange place then.

“There was still a mining industry, and the miners’ gala took place every year in Durham. Yet a lot of the students came from the southeast, and a lot of them had been privately educated. Durham was my education into Britain’s class structure and those signals, which I now understand. Long before somebody opens their mouth, you can tell what class they are, it is a funny sort of thing, especially in the northeast, to notice it.”

Alagiah spent a year with some friends trying to set up a national student newspaper. When that did not happen, he joined South, a London-based monthly magazine set up by Altaf Gauhar, the information secretary for the then Pakistan president, General Ayub Khan. He spent nine years working for South and, after several rejections, he finally joined the BBC in 1989.

“We got a producer, you had a camera crew, and the sound engineer, whereas as a print journalist you’re on your own. You’ve got a notepad, a little satchel, a pen and off you went,’ he told the GG2 Power List.

“When I came to write my first book, A Passage to Africa, I noticed that in my days as a print journalist, there were acres and acres of notes about what I’d seen, and what I thought about it. Then you get to the years at the BBC, and because it’s all on telly, and it’s being recorded, all you get are time codes and the odd name. I still miss the intimacy that we had in print journalism.”

Today, Alagiah is undoubtedly the most famous south Asian television news journalist in the country. Yet he told the GG2 Power List his heart remains in meeting people and telling their stories.

“About three weeks ago, after all this time of dealing with cancer, I finally reckoned it was time for me to put my walking shoes on and do a bit of reporting. We went out to Spitalfields (London). I was trying to tell a story of Covid and its effect on low-income countries. For example, one thing was the remittances, the money that families like yours and mine send back home, that’s been cut back.

“It was that it was an awful day, pouring down with rain. I had to do my piece of camera with an umbrella over my head, but I loved it because I was telling somebody’s story, and it wasn’t about me. I wasn’t there for 30 seconds or 20 seconds or whatever it is just looking at camera. I was telling a story trying to unravel somebody’s truth, and I just loved it.”

Alagiah is one of journalism’s most generous souls. He is a modest man. When you compliment him, he diverts by praising other south Asian colleagues.

“I’m 65, and I just look at the young people now, and the noise they make, and the talent they have coming in, and not just in news, but in entertainment, in our industry in the wider sense, and it’s just fantastic. You get, and I hope I don’t sound patronising, a young woman like Mishal Husain, who’s just brilliant at what she does. The Reeta Chakrabartis, the Clive Myries and Matthew Amroliwalas. There’s a whole load of people, and we’re all now role models, and if I played any part in opening that door, then that would be one hell of a legacy.”

We were only meant to speak for 15 minutes. Instead, an hour later, Alagiah respectfully asks to be let go. He wants to spend time with his granddaughter who could wake up at any moment from her afternoon nap.

“I’m in a good place, you know. I’ve got better at understanding vulnerability. I’ve got better at living in the moment. I have this mantra, I go to bed, and I just ask myself, so what do you think, George? You going to be here tomorrow morning? And I say, yeah, I think I am. I just wake up and get on with it. I’ve got better at doing that.”