THE union which represents judges has called for a parliamentary inquiry into the way the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) uses taxpayers’ money to fight legal cases.

For three months, Eastern Eye has used freedom of information requests to investigate court action against the JAC from unsuccessful candidates.

South Asian judges have told this newspaper that the JAC “intimidates and tries to frighten” candidates from complaining.

They have described the system by which they are appointed as “corrupt” and nothing more than an “white old boys club”.

Eastern Eye can reveal that between 2019 and May 2023, the commission spent almost £212,000 of public money on legal fees.

“At a time when we are learning that money has been withheld from making our schools safe from crumbling concrete, £200,000 of public money being used to go after individuals who are raising legitimate complaints appears not just unfair but a gross abuse of taxpayers money,” said senior organiser for the GMB union with responsibility for judges’ membership, Stuart Fegan.

“How is the authorisation of this money being overseen?

“It sounds to me that the oversight on all this is completely non-existent, and I’d call on parliament to look into this.”

Revelations

Eastern Eye can reveal that the JAC:

- spent more than £100,000 on a hearing which lasted two days.

- used three barristers to defend a single case.

- encourages secret references which cannot be challenged even if they are deliberately false or malicious.

- does not have any legally qualified people to deal with freedom of information requests.

- went into a tailspin when it was challenged over the use of its FOI powers.

Eastern Eye will also present evidence which suggests that the JAC may have given inconsistent testimony in an on-going court case involving a respected south Asian judge.

“Your findings reveal the extent to which the entire system is corrupt,” said one source who did not want to be identified for fear of being targeted by the judiciary.

“It’s a complete waste of tax-payers money because win or lose, the JAC can’t get any of the money back because of the no-cost rule when it comes to employment tribunals.

“How can anyone justify spending over 100 grand on a two-day hearing?”

Legal bills

What we discovered from our series of FOI requests is that five unsuccessful candidates took the JAC to court, two of whom are of colour.

So far, the five cases have cost the commission £211,980.57 in legal bills, and we understand three of the five are not over.

It may seem a relatively low amount, but sources we have spoken to have told us that it is normal practice for the JAC to employ three barristers to fight cases against a lone complainant.

In his case, the JAC hired three senior lawyers – a silk (King’s Counsel), a treasury counsel and a partner in a global law firm.

We understand that so far, the court has met in person twice and virtually for one hour.

That clocked up almost £102,000.

The case will cost the taxpayer even more when it is resumes in November for a seven-day scheduled hearing.

“They’ve got to do witness statements for their witnesses,” Ghosh told Eastern Eye.

“They’ve got to go through my witness statement, they’ve got to file skeleton arguments, they’ve got to attend for seven days, that’ll all costs.”

That may not be the end of the matter if either side decides to appeal the decision.

“It’s probably gonna go to appeal, all the way to the European Court, well, just imagine the bill then.

“The system of placing great weight on independent assessors who are High Court judges and whose names are made known to the shortlisting panel members means that the old boys’ network is the real method of appointment and not open competition.

“This [process] favours senior advocates in the High Court who are overwhelmingly white”.

Secret soundings

A second case involves Asif Malek, a judge whose public record demonstrates someone with a distinguished legal career.

This time Eastern Eye’s FOI requests revealed that the JAC was forced to reverse its decision not to appoint him when he applied for promotion to circuit judge.

The High Court heard Malek’s case for judicial review in May 2022.

“This involved an application for judicial review following the JAC decision not recommed (sic) the candidate for a Ciicuit (sic) Judge vacancy,” said the FOI response.

“The application for judicial review was withdrawn as further evidence came to light concerning the candidate’s character which enabled the Judicial Appointments Commission to reverse its decision.”

The second sentence appears to suggest that the commission wrongly believed something about the judge.

“The candidate was awarded costs by the High Court, which have yet to be finalised.”

The FOI response puts the JAC’s current legal costs at £9,133.60, but the final bill to the taxpayer could be 10 times that.

Eastern Eye was unable to speak with Malek about his case.

Once again Eastern Eye could not speak with Thomas, but we have seen court documents which make clear that she complained about bullying in the judiciary.

Our sources told us that by lifting the lid on the culture in the judiciary, which we have highlighted in our campaign, may have cost her promotion.

Court documents we have seen suggest that the JAC decided not to promote Thomas even though the assessment panels which interviewed her recommended she sit as both a civil and criminal circuit judge because of negative secret soundings.

By law, Eastern Eye must make clear that the judge in this case threw out Thomas’ claim, but she is appealing the decision.

We have seen evidence that the commission employed the so called “treasury devil” – the informal name for the first treasury counsel – Sir James Eadie KC.

His bill so far is £6,300 for just 21 hours’ work.

At the same time, for the same case, the JAC hired junior barrister, Robert Moretto at a cost of £3408 to the taxpayer.

But it does not end there.

The commission employed a third junior barrister, Natasha Simonsen, and her chambers billed £4320 for her time.

“So, let’s get this right,” said one of our sources, “the JAC hire three barristers to take on a district judge.

“Not only that, they also appoint the treasury devil, and they’re demanding Kate pays costs.

“If this isn’t overkill, then I don’t know what is, you don’t need three barristers on one case, you just don’t.

“They’re trying to intimidate her, and they’re wasting public money, and parliament must investigate.”

Our FOI request revealed that, “The application for judicial review was refused by the court, with the JAC being awarded costs.

“Ms Thomas has subsequetly (sic) appealed against the decision which is being considered by the High Court.

“We are not aware when that appeal will be heard.”

According to our FOI request the cost of the case so far is £30,380.08.

Costs

But we understand from our FOI request documents that the JAC is asking for almost £15,000 from Thomas – a single mother and primary live-in carer for her own mum – for the first part of her case.

“It sounds to be that they are using the prospect of significant costs being awarded against individuals asking legitimate questions,” said Fegan.

“They’re clearly trying to use that as a deterrent, it’s a deterrent towards people seeking transparency and seeking some form of justice.”

So where does the pernicious practice of secret soundings, highlighted so often by this newspaper, fit into Thomas’ case?

Eastern Eye was unable to speak with Thomas, but we have seen court documents from this March which prove that the JAC used secret soundings to assess her fitness for promotion.

Further, they show that Thomas believed that those who wrote did so because they were “motivated by malice, personal ambition, bias, discrimination or indeed any other reason”.

The judge who struck out her claim for judicial review, Dame Mrs Justice (Beverly) Lang said, “The statutory scheme provides that information and opinions about applicants for judicial office are to be given in confidence and remain confidential.”

She continued to make clear that Thomas could not see the comments made in the consultation exercise.

“The use of secret soundings is a massive problem,” one south Asian judge told this newspaper.

“It allows anyone who doesn’t like someone to make up stories.

“If you’re not clubbable, don’t go to the right dinner parties, don’t know High Court judges outside of work, you don’t stand a chance.

“And let’s face it, how many south Asians and ethnic minorities have access to those at the very top who can put in a good word.

“In effect, this is a white, old boys’ network, and you have to belong in that club and say and do the things they expect you to do and turn a blind eye to anything which smells off.”

Negative comments

We have also seen court documents which show that the JAC panel considered the negative comments.

“The panel report also considered the statutory consultation responses and noted that such responses were not fully supportive of your client,” Eastern Eye can reveal from a letter from the government’s legal department in June 2022.

The letter makes clear that because of the secret soundings the panel downgraded Thomas’ original grade which would have allowed her to be appointable.

“When the assessment of your client was specifically considered, the assigned commissioner indicated that the statutory consultation had provided some negative evidence in the competency.

“She also highlighted that the evidence at the selection day also included some negative evidence that was consistent with the negative evidence in the statutory consultation.

“She explained that although the panel report had identified that the statutory consultation contained negative evidence in the competency, when balancing the evidence as a whole they did not appear to have given proper consideration to the negative evidence observed on the selection day itself which was consistent with that.

“Other commissioners indicated that they had had the same concerns to those expressed by the assigned commissioner.

“All commissioners then took time to re-read the sections of the paper relating to your client, and a unanimous view was reached that the conclusions of the panels had been too generous so far as working and communicating with others was concerned.”

Disturbing evidence

We previously exposed how judges were taught to fail candidates, and this is a way of giving the judges a chance to say whatever they liked, whether it be malicious or favourable, without checks or scrutiny, according to sources.

Afterall, they said, who would go against the word of senior and influential judges?

We uncovered more disturbing evidence during our investigation.

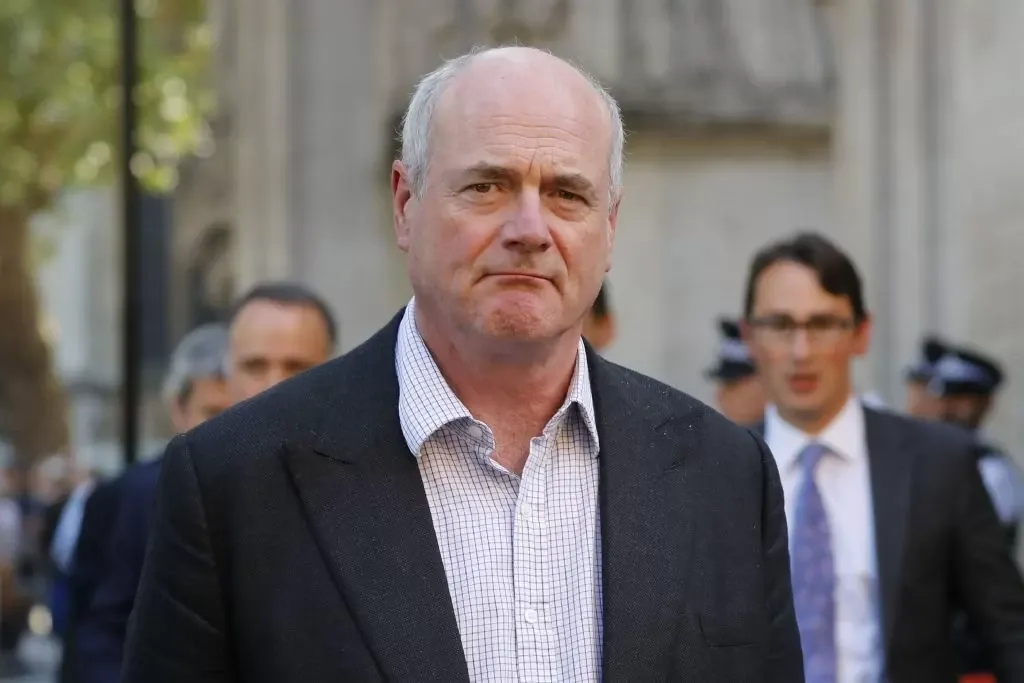

Eastern Eye has seen a document from 2016 from the lord chief justice, Ian Burnett, which makes clear those consulted should follow “the guidance”.

He also stressed that anyone could say anything about an applicant without fear, and no matter whether there is malice.

“Over the last three months I have read many examples of statutory consultation,” wrote Burnett.

“Very few appear to have been informed by the guidance.

“There is also a tendency to use coded language with judges perhaps believing that the JAC will read between the lines.

“Please speak with clarity and directly in statutory consultation because otherwise the point you wish to be understood will be missed.

“There is no risk that the content of statutory consultation (or indeed references) might filter back to disappointed candidates through feedback.

“Such feedback as is given by the JAC treats both forms of information as entirely confidential.

“Officials take great care to ensure that they do not use language from statutory consultation or references which might indicate its source.”

Eastern Eye approached the JAC for comment, but it ignored our requests.

Inappropriate system

“Those people decide who is and who isn’t appropriate to be a judge or dispense justice through this system, is that appropriate?” asked Fegan from the GMB union.

“Absolutely not, there’s no transparency, there’s no public scrutiny, and quite frankly, there seems to be little political and internal oversight scrutiny of this process, which is completely wrong.

“It was probably always wrong, but certainly in 2023 I think most people would consider that process to be, quite frankly, outrageous.”

It is a view confirmed by a former judge who blew the whistle on bullying and racism in the judiciary.

In this week’s Eastern Eye, Claire Gilham writes, “Privileged education, personal characteristics, professional connections and, yes, even family relationships remain the best predictor of appointment and promotion.

“Other judges, finding internal investigations biased, are litigating their complaints, and more are prepared to speak out.

“Cases which in the past would have been settled in private with hush money, are being reported in the press.

“What is emerging is a picture of failure to adhere to regulations and of collusive secrecy between agencies set up by parliament to act independently.”

Comment

How the “clueless” JAC went into a tailspin over whether it had the authority to stop information getting out

In the popular political drama series, The West Wing, the chief of staff to the president of the United States tells his team, “There’s two things in the world you never want to let people see how you make ’em: laws and sausages”, Barnie Choudhury writes.

The next part of our investigation reminded me of that.

It also made me think about the old journalistic adage: does what we are being told pass the “sniff test”?

And for me this story is smelly enough to warrant poking around further.

Our investigation has uncovered inconsistences in evidence which a current tribunal hearing may wish to consider in its deliberations.

It also showed a Ministry of Justice, Judicial Office and Judicial Appointments Commission which did not know who was responsible for certain decisions when it came to interpreting part of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

Judge Abbas Mithani KC has taken on the JAC and Information Commissioner’s Office because he believes they have failed to allow him data to which he thinks he is entitled under the act.

The tribunal panel reconvenes later this month (15).

Part of his case centres on the use of section 36 of the FOIA.

Put very simply, it allows public bodies to withhold information if the material were considered prejudicial to the work of those organisations.

But to use that get out clause the public body needs to have someone qualified to offer a “reasonable opinion” that it can deploy this exemption.

Qualified person

In open court and legal documents, Mithani established that the JAC did not have the proper authority because it did not have such a “qualified person”.

This may sound as if it were obscure minutiae and an unimportant point of law.

But it goes to the heart of whether we, the public, are truly being given information to which we are legally entitled.

Legally, journalists cannot influence judges or a legal panel operating without a jury.

They are above the fray of we, the prosaic public.

So, I write the following honestly held opinion based on our own FOI requests combined with various court documents.

Using freedom of information requests, we have discovered that between 2018 and 2021, the JAC invoked section 36 on five separate occasions.

Each time it said its then chief executive, Richard Jarvis, was the qualified person.

But when Mithani asked for proof that Jarvis had been given that power, the JAC realised it had one big problem which could throw into doubt the five previous requests.

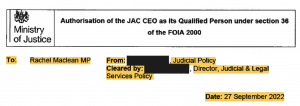

In court documents, the JAC said it sent a memo on the 27 September 2022 to the then justice minister, Rachel Maclean for the proper authority.

Remember the date – I’ll be testing you later.

Authority

We do not know who wrote the memo because the name has been blacked-out or redacted.

But we know it was someone from “judicial policy” who got clearance from “director, judicial and legal services”, so someone senior.

In it, the author wrote, “Since its creation in 2006, the JAC chief executive has acted as its qualified person where needed, and no concern or issue has ever been raised to his acting in this capacity.

“As part of a recent FOlA request, JAC were asked by legal advisers to provide evidence of the ministerial authorisation of its qualified person.

“Despite extensive searches, this cannot be found and does not appear to have ever been received.”

The memo makes clear that the JAC wanted authority, and that the Cabinet Office advised it should come from the minister.

But the e-mail exchanges leading up to this memo paint a picture of a JAC department in turmoil not knowing who did what or who was responsible for what.

The JAC’s head of corporate affairs, Ian Thomson, sent his first email to colleagues on 24 July 2022 at 8.43pm.

“In applying section 36 of the Freedom of Information Act, it has been our understanding that the qualified person within the JAC has been our chief executive,” he wrote.

“This was my understanding when I took over the role few years ago, and when I have looked back at previous requests, it seems to have been the situation since 2008.”

The email is heavily redacted, but the gist is that Thomson was seeking assurances that the JAC had done nothing wrong.

“I am sure that this is just a technical issue as it makes sense for our CEO to be authorised and it seems that the Information Commissioners [sic] Office has never raised objections to this, but I would welcome any advice, you or MoJ colleagues could provide,” he concluded.

Two days later, 26 July 2022 at 5.50pm, an unknown person from the Judicial Office or Ministry of Justice (MoJ) responded to Thomson’s email.

Ministerial permission

They make clear that after advice from “MoJ colleagues”, the JAC should get permission from a minister.

“A minister of the crown (and it makes sense for this to be an MoJ minister) should appoint a QP [qualified person], but l’ve discussed with colleagues within disclosure team at MoJ and we would suggest JAC contact Cabinet Office to query, as suggested by ICO.”

The following morning at 8.09, Thomson responded.

“I hope you have had the opportunity to see this issue that we have.

“[Name redacted], as you know has responded last night, suggesting that we contact the Cabinet Office for further advice.

“Before I do so, which I feel I might need to do so urgently, I was wondering whether you have any further comments/information on this.

“I am of course concerned that if I raise this with the Cabinet office [sic] it might open up other issues, so I thought it sensible to seek your views first.”

As part of my investigation, I consulted legal sources who asked why Thomson was “concerned” that this simple enquiry would “open up other issues”?

What were these “issues” of which Thomson was concerned, they asked?

Almost an hour later (9am), someone from justice responded, “Nothing further to offer on advice I’m afraid.

“It looks like a sub [submission] to LC [lord chancellor] requesting he appoints the JAC CEO as a QP will be ultimately needed if there’s no record of an existing JAC QP.”

The author also asks his or her colleagues whether anyone has “come across this before”.

Refusal

We are reading the first signs that the JAC never had the authority to refuse information using section 36.

Two hours later at 11.12am, the head of ALB [arm’s length bodies] strategy at the MoJ responded.

“Looking at the archived list on the ICO’s website, some MoJ ALBs are already covered and some are not which I will follow up with Carl on.

“I did see the following though and wondered whether it could be interpreted as the JAC chair as having the appropriate authority?

“If not, I agree re the note to the LC.

“I also think will need to confirm how the list of QPs is publicly updated.”

What is interesting here is that suddenly, rather than the JAC chief executive being the qualified person or QP, the writer of the email is hinting that it could be – could be – the chair.

My sources interpret this as civil servants who “don’t have a clue and are making it up as they go along to avoid public scrutiny and being embarrassed”.

The next email is from Thomson, almost a fortnight later, on 9 August.

“From my investigations, it does not appear that there is any formal record that the JAC chief executive is the qualified person for FOl cases.

“I am sure that this has always been the intention and it may be that provision is in place,, [sic] but we are unable to locate it.

“Therefore following Andrew/David’s advice, and also that of the Cabinet Office FOl team, I have prepared a draft submission that I would welcome your assistance on to ensure that is it submitted to the appropriate minister for considering [sic].

“I expect that there is information that you can add to this submission before it is in a fit state to go.”

This reminds me of the old proverb: the road to ruin is paved with good intentions.

According to my sources, this tells us that Thomson is driving the move for getting authority, someone who has no legal qualification, is not a solicitor or a barrister.

And as our FOI requests show, neither does any colleague who works with him at the JAC who deal with FOI requests.

Technicality

The next email of significance is one from an unknown author from justice on 15 August 2022.

The unknown author wrote, “Can legal be persuaded that you answer the FOl as you would have done in the past (as the authorisation looks to be an overlooked technicality), on the proviso you get the authorisation to follow?

“Is this time critical (is it an open FOl and when’s the deadline?) or are you able to respond to the applicant in a different way?”

“An overlooked technicality” – really?

Is this the way democratic government bodies are supposed to work?

Under an hour later, Thomson responded, “However as we could use another exemption in this case, we could at least respond, and if a further review was undertaken, if we had the authority we could apply that point then.

“It is only time critical now if we get further FOl requests and the only exemption we could use would be section 36.”

My sources told me that it clearly demonstrates the mindset of the justice department when answering FOI requests – to obfuscate and spin.

Almost a month later, 13 September 2022, our FOI evidence shows that the justice department is no closer to deciding who the qualified person is.

The lack of decision making is put down to the parliamentary recess, appointment of a new lord chancellor by a new prime minister, Liz Truss, and the death of the queen.

Thomson checked 10 days later, and again, no decision, and you sense panic.

“The FOl is overdue and we sent holding replied [sic],” he wrote to his colleague in justice.

“So in essence we need the authorisation as soon as possible.”

Ministerial permission

Finally, on 27 September, it looked as if someone had found out who could approve authority – the justice minister.

But.

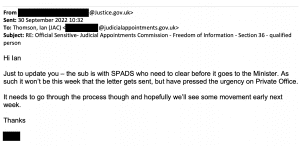

Three days later, 30 September 2022, Thomson’s unnamed colleague had some bad news.

“Just to update you – the sub is with SPADS [special advisers] who need to clear before it goes to the minister.

“As such it won’t be this week that the letter gets sent, but have pressed the urgency on private office.

“It needs to go through the process though and hopefully we’ll see some movement early next week.”

This raises a simple question.

How could it be that the panel in Mithani’s case has documents which show a memo was sent to the minister on the 27 September 2022, when the email trail demonstrates that was not possible?

What we do know from court documents is that the minister finally gave her approval for authority to have qualified person status to the JAC boss on 10 October 2023.

Why is this significant?

Details

I have waded through pages and pages of legal documents.

Remember, Mithani’s case is not just against the JAC but also the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

The ICO based its decisions on what it was being told, or not told in this case, by the JAC.

In a letter dated 3 October 2022, Steven Ball from the JAC wrote to a Helen Jarman, a senior case officer at the ICO, explaining the decision-making process regarding Mithani’s FOI requests.

At no point in that email did Ball mention that the JAC did not have an approved qualified person to invoke the section 36 exemption.

I am not saying this was a deliberate omission.

But the tribunal panel in Mithani’s case should consider whether the ICO acted with full knowledge, because it appears that the Information Commissioner’s Office believed that the JAC had powers to invoke the exemption.

The fact the JAC did not have the authority is proven by the email trail I obtained under freedom of information.

Finally, I found another matter which troubled me.

Once again, it is for the tribunal to decide the importance, but as a journalist, words and details are important.

Follow me on this.

Scrutiny

In his witness statement in the Mithani case on 15 March 2023, Thomson wrote, “At the time we were considering this request, we understood Dr Richard Jarvis to be the qualified person for the purposes of this provision, as the CEO of the JAC.

“However at a later stage when we were searching for the ministerial authorisation pursuant to s.36(5) (in relation to another matter), we were unable to locate a copy of the authorisation on file.

“Therefore as a precaution, a new ministerial authorisation was sought, and this was granted on 10 October 2022.”

Yet the emails I’ve obtained under freedom of information suggests there was never any authorisation for anyone to act as a qualified person.

Remember, Thomson wrote to colleagues on 9 August 2022, “From my investigations, it does not appear that there is any formal record that the JAC chief executive is the qualified person for FOl cases.”

Remember, earlier on 9 July 2022, an MoJ official wrote, “I did see the following though and wondered whether it could be interpreted as the JAC chair as having the appropriate authority?”

My question is quite simple – how could this be a “new” ministerial authorisation when there wasn’t one in the first place?

Once again, I’m not suggesting Thomson is misleading the panel.

My job as a journalist is to observe, ask questions, and hold power to account.

What the Mithani case has shown is how poor our justice department is; how public bodies try to get around the Freedom of Information Act; and how words said and unsaid could potentially affect outcomes in legal cases and when we, the public, are seeking a version of the truth.

“We’re being muzzled”

During our investigation, this newspaper spoke to several south Asian and white judges who said they were “extremely concerned” to speak out because the “Judicial Office is clamping down on what we can say”.

“We’re no longer allowed to say anything which isn’t pre-approved,” said one senior source.

“The stories you’re doing are great and just the tip of the iceberg, but if we are identified, they’ll come at us, guns blazing.

“What you’re finding out is great because sunlight is the best disinfectant.

“If we’re being muzzled and told what to do, how can we protect or uphold independence and justice for those who come before us?”

The latest edict from the lord chief justice should chill those seeking and dispensing justice to the bone, several sources told this newspaper.

The updated guidance is clear.

“Judicial office holders should be aware, however, that participation in public debate on any topic may entail the risk of undermining public perception in the impartiality of the judiciary whether or not a judicial office holder’s comments would lead to recusal from a particular case,” the document stated.

“This risk arises in part because judicial office holders will not have control over the terms of the debate or the interpretation given to their comments.”

Another source likened it to the fifth Harry Potter novel.

“In the Order of the Phoenix, the ministry of magic sent one of its own to interfere with Hogwarts,” they said.

“Well, the Ministry of Justice and the civil service are well and truly embedded in the judiciary.”

Concerns

The Judicial Support Network (JSN), a confidential association for judges co-founded by Judge Kaly Kaul KC, is concerned with the latest missive.

“I co-founded the JSN because of the climate of fear that I felt pervades the judiciary, and because of the way many of us have been treated but did not dare talk about.

“We have received over 250 different allegations of misconduct by judges on judges.

“Judges became increasingly confident in raising concerns with us officially and new policies were put in place, but we have a long way to go.

“Am I to be disciplined for saying that, on the basis that it is controversial?

“The judicial communications office can put out any material it chooses, to create any impression it chooses as to the collective position of ‘the judiciary’, but if that is inaccurate or lacks balance, are we really not allowed to comment?

“The UK is party to UN conventions guaranteeing the independence of the judiciary and judges, and we are part of the Commonwealth of Judges.

“Is this the precedent that we wish to set when we all strive for fairness and transparency in our societies?”

Other judges have contacted Eastern Eye and explained that they need freedom of expression “so we can comment without fear or favour and remain truly independent of the MoJ (Ministry of Justice) and civil servants.”

“A number of judges are facing the mounting abuse of lawyers over the immigration backlog,” said one who wanted to remain anonymous.

“One I know has major and shocking information which as a result of the new policy they are finding it hard to go public with, despite enormous public interest in telling the truth over why the backlog is mounting.

“They’re just too frightened to put their head above the parapet and say anything, and that’s worrying.”