SHIRIN WHEELER has talked to Eastern Eye about the book she has written about her father, Sir Charles Wheeler, who was once the BBC’s star foreign correspondent.

He had served in Delhi, Berlin and Washington, before returning home to report on the multicultural Britain in which he always believed and which he said “is here to stay”.

It was while he posted in Delhi from 1958 to 1962 that met Kuldip (‘Dip’) Singh, a glamorous Sikh woman who was social secretary at the Canadian high commission.

The couple married in Delhi on March 26, 1961. Their daughters, Shirin and Marina, were born in Berlin in 1963 and 1964 respectively.

Charles died, aged 85, in 2008, and Dip, aged 88, in February 2020 at her cottage in the village of Warnham, near Horsham, West Sussex.

Marina has written a book about how her mother fled Sarghoda in Punjab, now in Pakistan, just before Partition, when she was 14, in The Lost Homestead: My Mother, Partition and the Punjab.

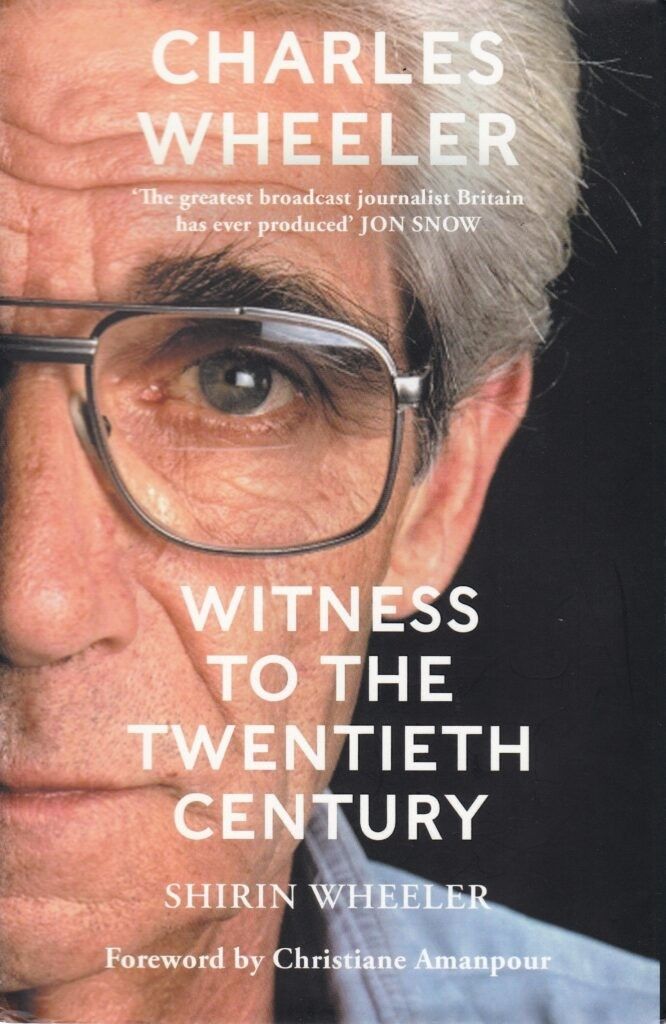

Shirin, whose book is called, Charles Wheeler: Witness to the Twentieth Century, remarked: “Marina wrote a book about my mother. And I’ve written a book about my father. There’s a moment where their stories overlap. I found some letters from my mother to my father, which are very tender, loving letters.”

Shirin said: “Charles, I had to learn to refer to as ‘Charles’, as opposed to ‘my father’ or ‘Fa’ – as Marina and I called him. That’s part of the challenge of writing a book about a parent.”

In 2012, the Indian Journalists’ Association in the UK honoured Charles with a posthumous lifetime achievement award, with an inscribed Waterford crystal bowl handed over by the then Indian high commissioner, Jaimini Bhagwati, to Shirin and Marina.

The sisters then did an engaging double act on their father’s journalistic career, which Shirin has written about in detail in her book.

Charles did not want to spend time writing his memoirs, as he always wanted to remain a reporter. In fact, he resigned his staff job and turned freelance as a way of resisting pressure from the BBC to go into management. Shirin did not want her book to be a hagiography, which is why she has included critical internal memos in which Charles’s bosses at the BBC said he was “editorialising” too much by putting his personal opinions into his reports.

At first, Shirin thought she would put together a historical archive of Charles’s despatches, a project she still wants to do with a university. Charles himself stored many of his old scripts on top of a wardrobe at home.

Explaining the genesis of the book, she said: “I was talking to my daughter, who was doing A level history, and to her friends. They were talking about the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of communism, the American civil rights movement, the birth of independent nations after colonialism. And I said, ‘Hey, your grandfather covered all these stories.’

“The girls were enthused at the idea he had actually interviewed Martin Luther King, (and) he had spoken to Mrs (Indira) Gandhi, the daughter of Nehru, when she was a young woman. Pretty soon, it morphed into the idea of a book. It suddenly made me think I have to get this story down and share it with potential journalists of the future.

“So I gained access to the BBC archives. My husband [Dan Colwell] proved to be a great source of material on top of my own memories. He had kept a diary, every single day, for the last 40 years. And within that diary are conversations with Charles, about his childhood in Germany, and his experience in 1945 when he was part of an intelligence gathering naval commando unit, a maverick group of men created by Ian Fleming, who went on to write the James Bond stories.”

Shirin’s book has got a big section on India. In Delhi, Charles covered Nehru, the flight of the Dalai Lama from Tibet and his arrival in India, and the first state visit since independence by the Queen and Prince Philip in 1961. He was so fed up with the extended royal tour that he was heard to remark, “I wish that bloody woman would go away.”

For the next five years he was persona non grata at Buckingham Palace (but when the Queen handed Charles his knighthood 45 years later in 2006, she told him how much she admired his work).

Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) threatened to leave the Commonwealth after Charles described the country’s new prime minister, Wijeyananda Dahanayake, as “an inexperienced eccentric at the head of a cabinet of mediocrities”.

Normal diplomatic relations were not restored until the British prime minister Harold Macmillan expressed his regrets on top of the BBC’s apology.

After Berlin, Charles was posted to Washington from 1965 to 1972 as chief North America correspondent.

“That was the childhood Marina and I experienced in an America alight with protest and change: the civil rights movement, the peak of Martin Luther King, then, of course, his assassination, and then presidents Johnson and Nixon, culminating in Watergate,” remembered Shirin.

During the civil rights riots in America, Charles’s radical streak was clear in a piece to camera when he reflected what the black people were saying: “‘They push us around, they arrest us for nothing , they call us Niggers, they say we stink, they insult our women. We’ve had this for years as long as we can remember, and now the point simply came when somebody decided we wouldn’t take it any more.’”

According to Shirin, the US riots affected him deeply. “When he came back to Britain, Charles had not lived in the UK for decades. He worked with Gareth Peirce, a lawyer who defended the ‘Birmingham Six’ and the ‘Guilford Four’ and had also taken up the case of some of the [black] men in Notting Hill. The police had beaten some of them. And he saw in Britain definitely some of what had been going on in the States, though obviously not the extreme situation he had found in the south. But clearly, there was institutional racism from the police. He covered it. He did a story on Stephen Lawrence.

He did a number of stories about the Asian community and multiculturalism. He was a firm believer in that. Those stories spoke to him throughout his life.”

high commissioner Jaimini Bhagwati

The book’s foreword has been written by the TV journalist Christiane Amanpour, who considered Charles to be a mentor. Amanpour, said Shirin, has defined the role of the correspondent, as epitomised by Charles, “to hold power to account, not to be intimidated by authority, but at the same time to believe that the job of the journalist is to give voice to people who are marginalised”.

Technology that assists journalists had been transformed during Charles’s career. He had once filed from Sikkim in the Himalayas using morse code “but he was also one of the first to use satellite TV from Washington,” Shirin pointed out.

She continued: “But there are some enduring values in journalism that remain. And I hoped that would be one of the ideas this book could convey through his stories and values. This is at a time when journalism and objective truth are under attack.”

Charles Wheeler: Witness to the Twentieth Century by Shirin Wheeler is published by Manilla Press. £25