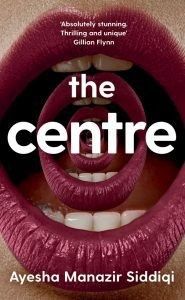

DEBUTANT writer Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi said she has tried to “dismantle the idea of great literature” with her first novel, The Centre.

The novel’s protagonist, Anissa Elahi, is a Pakistani Muslim woman living in London who dreams of being a translator of great works of literature. When her white boyfriend, Adam, who is fluent in almost a dozen languages, learns Urdu in just 10 days at mysterious place called The Centre, Elahi enrols to learn European languages because, in her mind, that’s where great literature has come from.

“I tried to dismantle that idea of what she (Elahi) considers great works of literature. I think that points to my own journey of trying to dismantle the idea of great literature in order to create a story that feels real to me,” Siddiqi told Eastern Eye.

“I wanted to fight against societal ideas of ‘this is good literature, and this is not’ and ‘this is a legitimate writer, and this is not’. In that way Anissa’s journey, even though it is about translation and mine is around writing or literature – there are some parallels.”

Siddiqi said race played a part when it comes to what is considered great literature. When she wrote stories as a child, she revealed that her characters would have blonde hair and wore western attire – even though she grew up studying in tuition centres in Pakistan.

“We feel largely western literature is wonderful. Growing up, what did that do to our psyche – for society to tell us this is literature, this is what intellectualism looks like? It makes us feel insecure or silent or like we can only inhabit certain spaces. Or, if we do inhabit that space, sometimes what we can end up doing is a kind of imitation or writing for the white gaze,” she explained.

“There’s almost this white supremacist system that has led us to believing that knowledge and intellect and so-called literature only comes from these places.”

Siddiqi’s novel explores other themes that the author experienced since moving to London as an 18-year-old student. She has been a writer, editor, playwright as well as an occasional translator for more than a decade. “

This super mysterious language school promises fluency in any language in just 10 days – but at a secret cost. And you find out what this is over the course of the novel. There’s a few twists and turns in the work,” Siddiqi said.

“It’s about many things. It’s about gender, race, sexuality and class, about cultural appropriation, assimilation and the struggle for self-actualisation.”

At the centre, Elahi first studies German, then Russian. Eventually her dream comes true and she turns into a polygot who becomes a hit in the British literature circles. The joy doesn’t last for long though, as she becomes uneasy with her new life and starts to question her identity and her sense of belonging – is her mother tongue English or Urdu?

“Being someone from a Pakistani background, being a woman, being Muslim – being all of those things, you find the dominant culture in this country wants a certain narrative from you. How do you evade that and how do you kind of battle with that?” said Siddiqi, while reflecting on herself and the lead protagonist in her novel.

Elahi barely gets to speak Urdu, having grown up in an upper middle-class family in Karachi and then most of her adult life in London. When she travels back to Pakistan with Adam to visit her parents, he is praised for being able to speak Urdu fluently, which angers Elahi as she feels like her mother tongue has been “stolen” from her.

Siddiqi admitted that reflects the issue of cultural appropriation – when a dominant culture takes something from a minority one without understanding the true nature of what they have taken.

“I have this habit of always saying ‘Bismillah, Inshallah, Alhamdulillah’ – that’s me staying with myself and my culture,” said Siddiqi.

“Generally, I do speak in English, so it’s not a big problem. But I find myself like censoring myself or just whispering ‘Bismillah’ before I start to talk.

“Sometimes, I worry, is that because of shame? Why do I have to tone down certain parts of who I am?

“When I find myself saying it in my head or whispering it, I feel that is a compromise I am making and that’s painful. But if I were to say it around white people, they might think I’m like self-exoticising.”

She added: “But I don’t like it when others (non-Muslims) start saying it (Bismillah). It really annoys me because that’s cultural appropriation and that is a big problem and has risks.”

Siddiqi said she made it a point to use Urdu in The Centre.

“I have to say, it’s very beautiful that nobody – not the publisher, nor the agent, nobody – questioned my use of Urdu in the book. I don’t believe this would have happened 10 years ago,” she said.

“The fact that it could remain is very important to me because what it does is it allows me to write or speak the text as if it’s a conversation with my mother or my sister or my best friend. And that allows for a kind of intimacy that lets me go deeper with my writing.”

She added: “The conversation has changed around using our own languages in our books. People say, ‘if you don’t understand it, you can look it up’.

“But I think we can go a step further from that. I think we can say that if you don’t understand it, maybe it’s not for you. And maybe let it go.

“I think again, this is the entitlement of the dominant culture that they feel like everything is for them and you have to translate everything for them. But it’s ok to have your own things and it’s ok to protect those things and it’s ok to have conversations among ourselves.”