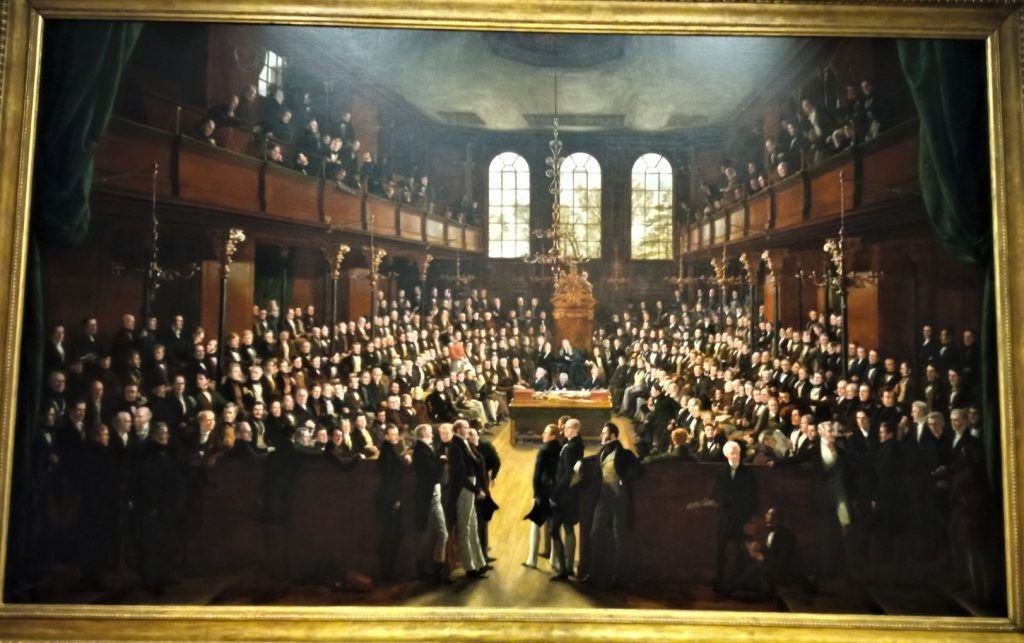

STANDING in front of the vast painting of the House of Commons in 1833 by Sir George Hayter at the National Portrait Gallery brought home how much Britain has changed.

Perhaps someone should execute a similar canvas with Rishi Sunak at the centre of things, with the chamber dotted with black and Asian members of parliament.

A little tip to Eastern Eye readers: the gallery reopened last week (Catherine, the Princess of Wales, who is quite a good photographer herself, did the honours) after a three-year renovation costing £41.3 million. It is worth spending three to four hours in the gallery, where the collection of portraits, spanning six centuries, tells “the story of the United Kingdom through portraits, from the Tudors to today”. Entrance is free of charge.

Habib Rahimtoola

There are many more women on display and the radical rehang from the gallery’s collection of 4,000 paintings, sculptures and miniatures, as well as 8,500 works on paper reflects such recent developments as Black Lives Matter.

Britain’s close relationship with India is also apparent, taking in the period of colonial rule, the war years, the fight for Indian independence and the growth of the Indian community in the UK.

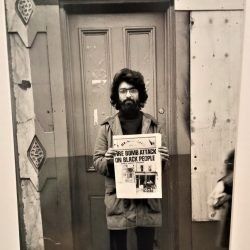

I was pleased to see photographs of Farrukh Dhondy and the late Mala Sen from their activist days in the East End of London. In the section called “History Makers Now”, there is a portrait of the actor Riz Ahmed. On a wall nearby was projected a giant image of Malala Yousafzai – in fact, in the gallery workshop I bought a postcard of her black and white portrait, along with those of Lord Byron, Charles Darwin and Winston Churchill (£1 each).

Having entered the gallery through the grand new entrance in Ross Place, I wanted to try out the ground floor café where there used to be a bookshop, but deferred it to another day because a queue had formed. As I wandered around the gallery, which now feels light and airy, I made a note – in no particular order – of the paintings or photographs of Sir Salman Rushdie by Bhupen Khakhar; Noor Inayat Khan by Felix Man and VS Naipaul by Bill Brandt.

There was a bust of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, by Jacob Epstein, adjacent to a photograph of Nehru’s sister, the diplomat Vijay Lakshmi Pandit, though the caption missed out the fact she was the Indian high commissioner in London from 1955 to 1961. Next to her was a photograph of Begum Zubeida Habib Rahimtoola, when her husband was Pakistan’s first high commissioner in London in 1947.

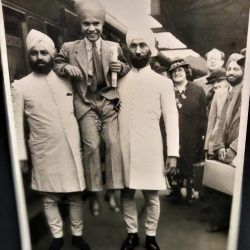

There are press photographs of Mahatma Gandhi from a visit to the UK in 1931, when he was warmly welcomed by local weavers in Lancashire, and of the actor Sabu (star of such films as Elephant Boy and The Thief of Bagdad) with his bodyguards as he left Britain for America in 1938.

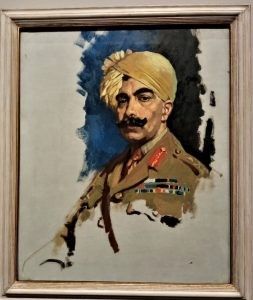

From the war years, there is a portrait of Ganga Singh, Maharaja of Bikaner, who placed the resources of his state at Britain’s disposal throughout the First World War and was the first Indian to become a British Army General.

There is also one of Jayapal MR Jayakar, who came to study at Oxford in 1932, but was commissioned as a Pilot Officer in the Royal Air Force in 1939.

I once visited India’s Eton – the Doon School in Dehradun, which has a “Skinner’s Field”. The gallery has a portrait of the man after whom it is named – Lt Col James Skinner (1778-1841), the son of a Rajput woman and a Scottish East India Company army officer.

There is also a painting of Munnoo, who was born in Madras (Chennai) in about 1795 and became a favourite servant of William Hickey (1749-1830), who played a prominent role in the judicial administration of British India for 30 years.

Captions set the period of empire in a more balanced fashion to indicate the rulers exploited the ruled: “People living between 1850 and 1914 witnessed the rapid expansion of the British Empire. Known as ‘the empire on which the sun never sets’, it covered almost a quarter of the earth’s land surface and, at its peak, ruled over 458 million people.

Bikaner

“As the empire grew, Britain became extremely wealthy at the expense of the countries and cultures it colonized. Besides goods and money, people also moved in multiple directions across the empire. Whether they were moved by choice or taken by force, their experiences were highly varied and deeply personal.”

There is a painting from 1840 of the “Anti-Slavery Society Convention”.

“During the reign of Queen Victoria, Britain’s empire became the largest in the world. This room explores how portraiture was used to promote the British Empire as the embodiment of global power, civilization and superiority,” read another caption.

There are images of Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of Bengal from 1772–1785; of the victorious Robert Clive with Mir Jafar and his son Mir Miran after the Battle of Plassey in 1757; and The Relief of Lucknow which “celebrates Britain’s suppression of a mass uprising that took place in India between 1857 and 1858”.

The latter painting is by the propaganda artist Thomas Jones Barker, who “became famous for producing large paintings that promoted the British Empire and its values”.

Also included is an image of Rani Lakshmi Bai of Jhansi, a “warrior-princess” who “became a symbol of Indian resistance to British colonial rule”.

It is worth taking note of the caricature of Duleep Singh, the last Sikh Maharajah who was a handsome boy of 15 when he gifted the Koh-i-Noor diamond to Queen Victoria, but by 26 had become plump and balding.

There is a picture, too, of his wife, Maharani Bamba Duleep Singh (1848-87), who was “the illegitimate child of a German banker living in Egypt and an enslaved Ethiopian woman”.