THE horror stories of ethnic violence emerging from the northeastern Indian state of Manipur have greatly distressed the British artist, Marcus Hodge, because the place had appeared like a peaceful paradise to him when he was there in November last year painting polo ponies.

Hodge was in Imphal, the state capital, witnessing a local form of polo, called Sagol Kangjei, which gave rise to the modern form of the game.

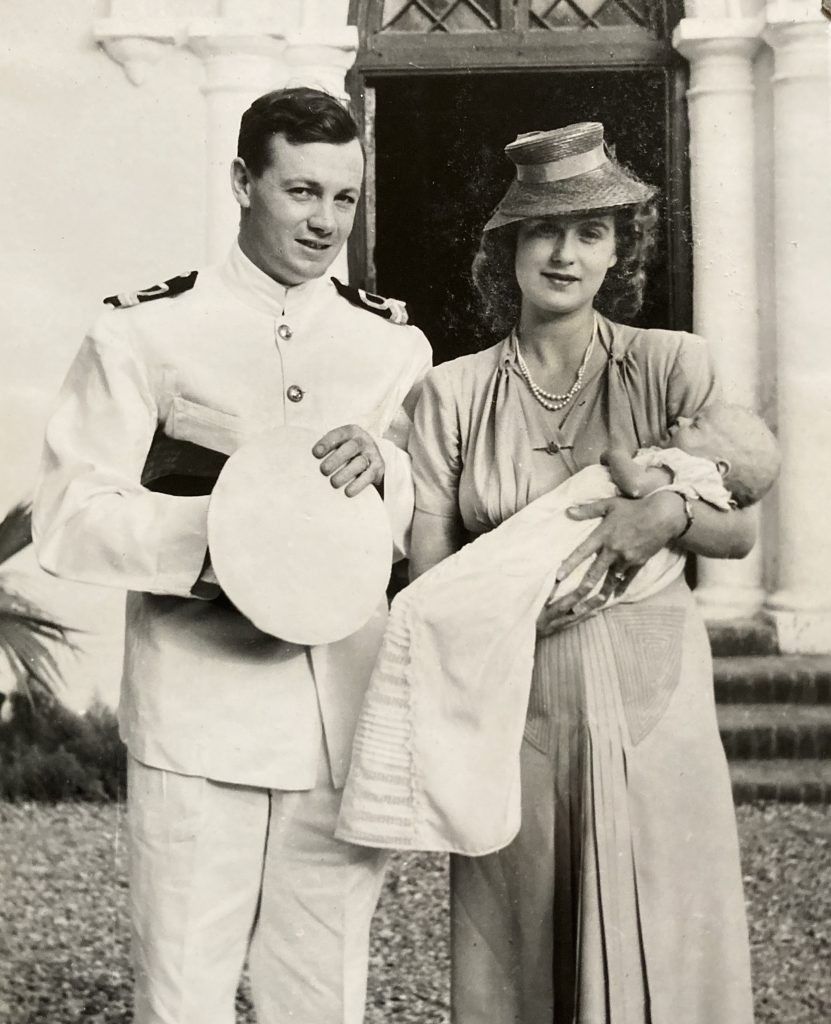

He was on probably his 15th trip to India, which has inspired much of his art and where his maternal great grandparents, Alan Eden and Letitia Muriel Eadon and grandparents, Tony and Joyce Pigou, spent a good part of their lives.

The artist, who was himself born in the UK in 1966, lives and works in the quiet Oxfordshire village of Appleton.

As a child, he was brought up on Indian tales told by his grandmother, who often had curry instead of roast served at home after coming back to England.

In November 2022, Hodge went to India for a month, when he spent five days in Imphal and didn’t pick up on the impending tribal violence between the majority Meteis, who are largely Hindu and constitute about 53 per cent of Manipur’s 3.3 million population, and the minority Kukis, who tend to be Christian and together with the Nagas make up the rest.

This time the violence appears to be rooted in ethnicity, rather than religion. Violent clashes broke out in Manipur after a “Tribal Solidarity March” was organised in the 10 hill districts on May 3 to protest against the Meitei community’s demand for Scheduled Tribe status. The clashes were preceded by tension over the eviction of Kuki villagers from reserve forest land, which had led to a series of smaller agitations.

At least 130 people have been killed and 400 wounded since May. More than 60,000 have been forced from their homes as the army, paramilitary forces and police struggle to quell the violence. Police armouries have been looted, hundreds of churches and more than a dozen temples ruined, and villages destroyed.

Currently, 20 of Hodge’s abstract paintings, all inspired by India (apart from a couple in Nepal), including Tantra, have been exhibited online by John Adams, who had a gallery in Notting Hill, but went digital during the pandemic. But Hodge also does representational paintings, which is why he was in Manipur.

He said: “At the moment I’m doing a commission for the British Sporting Art Trust to do any subject I liked to do with sports. And so I chose the history of polo, which starts out in India, as my subject.”

Hodge is doing a “very large diptych, part of which is English polo, but part of the imagery is the game of Sangol Kangjei, with some of the original players. I’m hoping to have it done in about another six weeks’ time. But it’s then due to be opened in the National Horse Racing Museum in New Market, which they share with the British Sporting Art Trust. And then I think Queen Camilla is coming to unveil it.”

People have various theories on how polo began, but Hodge said its origins date back to Persia in the 6th century with “100 or 200 people per side”.

Then the Mughal Emperor Akbar apparently brought it to India, built a polo ground outside Fatehpur Sikri near Agra, and “was the first person to pen some actual rules”.

Then the game migrated in different directions. In 1858, British army officers from Calcutta saw the game being played by tea plantation workers and farmers. They were very taken with “Sagol Kangjei”, as it was called, returned to base and set up the Calcutta Polo Club in 1864 – “and that was the beginning of modern polo”. Hodge’s abstract paintings, which is what he wants to focus on, are done on site. But for the polo painting he would do when he was back home in Oxfordshire, he made sketches and took “some wonderfully dramatic photographs of these men flying around on their horses. And they’re very beautiful little Manipuri polo ponies.”

He had been given an introduction to the president of the Sagol Kangjei Association, which was holding “great big national festival championships. All the politicians, including the state’s chief minister, were there for the huge celebrations”.

Hodge detected no hint of trouble: “Nothing, absolutely nothing. I had been in Jaipur and Delhi – and Kolkata for four or five days and struggling with the pollution and the noise. And then you fly up to Imphal and it’s just beautiful. The landscape around there is breathtakingly lovely. And the people were just incredibly friendly, especially as I was the only European face to be seen anywhere during my entire time there.”

Hodge is currently reading a book on the 1947 Partition of India and finds echoes of the past in the present. “And I thinking, crikey, same old story. You’re reading an interview with somebody who is saying, ‘We’ve fled for our lives. My father-in-law was beaten to death. And they burned the shops down.’ And these are people that they have lived next to, worked with, been friends with for years and years and years. And everybody’s lost their head and got whipped up and gone crazy, and just turn to violence.”

He will be going out to India again in the next few months, but this time it will be partly to check up on a charity that he supports. It is for orphaned or abandoned girls, Sheela Bal Bhavan, in Jaipur, with a smaller offshoot in Nainital, a former British hill station in Uttarakhand. One of the girls, who arrived when she was six, is now nearly 30, “a wonderful young woman and she calls me ‘Dad’”. Since the pandemic, “organisationally, it (the charity) has suffered quite a bit,” Hodge said.

The home in Nainital was set up initially to look after three babies. “A few years ago, I opened a book and there was a picture of my grandmother on the first page by the lake in Nainital. Now isn’t that strange? It feels like something has gone full circle. There’s a deeply emotional connection.”

His interest in Tantric art goes back many years to a trip to Paris. He discovered 17th century Tantric Rajasthani paintings which were “used as an aid to meditation and prayer. I was blown away by these images.”

The Art Newspaper explained the concept to its British readers: “In Tantra and Tantric art philosophy, ritual, symbolism and iconography are very closely connected. Tantric art is a means to spiritual development and realisation. It comprises tranquil renderings of abstract forms like the universe, Yantras (mystical diagrams) on one hand – and violent, emotional iconographic images portraying the terrifying aspects of Prakriti on the other.”