“WHO was Winston Churchill – the saviour of his nation or a racist imperialist?”

This is the rather blunt question that will be examined in the opening session of a debut literary festival next month, to mark the 70th anniversary of Churchill winning the Nobel Prize for literature.

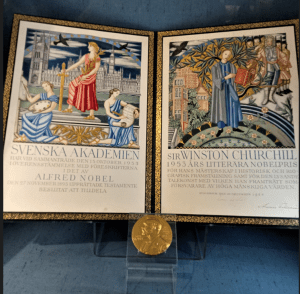

It was given for his “mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values”.

What is remarkable is the venue – the festival is being held at Chartwell, Churchill’s home near Westerham in Kent, from September 8-10. It will examine the controversial aspects of Churchill’s character, such as his hatred for Mahatma Gandhi and his hostility to the idea of Indian independence.

Eastern Eye readers will find Chartwell a revelation. This is where Churchill did much of his writing, refreshed by champagne and cigars and also his painting, for he took lessons from Walter Sickert and was an enthusiastic amateur artist.

“When I get to heaven, I intend to spend a considerable portion of my first million years in painting and so get to the bottom of the subject,” he said in an interview in 1946.

Those who want to understand why Churchill is held in such reverence by the English certainly ought to pay a trip to Chartwell, a fast train ride from London Bridge and then a taxi from Sevenoaks.

Visitors to Chartwell tend to shuffle silently from room to room as though they are in a temple. The place is like a shrine to Churchill – there are his photographs with world leaders; his books, mostly on history – he modestly said, “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it”; gifts, including a gold dagger from King Abdul Aziz ibn Saud; and, of course, his cigars.

Curiously, the place appears to have been cleansed of anything Indian.

It’s baffling that a man with such a global vision, who could detect the danger from the Nazis ahead of his contemporaries, firmly positioned himself on the wrong side of history when it came to independence for India.

Churchill’s line even in 1942, only five years before Indian independence, was: “We have not entered this war for profit or expansion. Let me, however, make this clear: we mean to hold our own. I have not become the King’s First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.”

Chartwell, which Churchill loved and bought in September 1922, is very much an English family home. He and his wife Clementine occupied the property until just before his death in January 1965.

The first Chartwell Literary Festival will have a 90-minute launch event on September 8 with Allen Packwood, the director of the Churchill Archives Centre at Churchill College, Cambridge, as well as the historians Dr Victoria Taylor and Prof Gaynor Johnson.

All three are among contributors to The Cambridge Companion to Winston Churchill, which has been edited by Packwood and was published earlier this year.

The opening session will reflect the theme of the book: “Viewed by some as the saviour of his nation, and by others as a racist imperialist, who was Winston Churchill really, and how has he become such a controversial figure?”

It continues: “Combining the best of established scholarship with important new perspectives, this Companion places Churchill’s life and legacy in a broader context. It highlights different aspects of his life and personality, examining his core beliefs, working practices, key relationships and the political issues and campaigns that he helped shape, and which, in turn, shaped him.

“Controversial subjects, such as area bombing, Ireland, India and Empire are addressed in full, to try and explain how Churchill has become such a deeply divisive figure. Through careful analysis, this book presents a full and rounded picture of Winston Churchill, providing muchneeded nuance and context to the debates about his life and legacy.”

One of the chapters in the book, by the former Indian diplomat Kishan S Rana – he won’t be at the festival – is headed, “Churchill, India and Race”, which indicates just how much the debate on Churchill has shifted in recent years.

Indian historians are divided on whether Churchill was responsible for aggravating the effects of the Bengal Famine of 1943 in which three million Indians died.

Other subjects covered in the festival include Amongst the Ruins: Why Civilisations Collapse and Communities Disappear; Untold Stories of the Second World War; The Arab World from 1922 to the Present Day; Remembering and Forgetting China’s Cultural Revolution; Stories from the SAS Great Escapes; Korea: A New History of the North and the South; Attack Warning Red! Talking Nuclear; Cinderella Boys – Unsung RAF Heroes; Resistance: The Underground War in Europe, 1939-1945; Beyond the Wall in East Germany; and African and Caribbean People in Britain: a History.

Chartwell’s curator Katherine Carter said: “Winston Churchill’s home in Kent was his factory of words. From speeches and correspondences to articles and books, Chartwell gave Churchill the perfect place to consider world events, both as a journalist and historian, and respond with his critically acclaimed writings. “It is fitting that the place that inspired his pen more than any other is to host the first Chartwell Literature Festival in celebration of his Nobel Prize-worthy words.”

A renowned orator, successful journalist, gifted painter and one of the 20th century’s most prominent statesmen, Churchill was a prolific author with 43 book-length works, in 72 volumes, published over the course of his lifetime (1874-1965) and posthumously.

Chartwell’s general manager, Chelsea Pettitt, who previously worked as head of arts at the Bagri Foundation, commented: “We are thrilled to host such a vibrant range of fantastic speakers and guests at the family home of Sir Winston Churchill for this very special occasion. These voices represent a broad range of backgrounds and perspectives, shedding light on the unexplored and lesser-known narratives which still impact upon us today.

” The National Trust, which is eager to promote diversity, is especially keen for Eastern Eye readers to consider becoming members and also visit its properties, including those with Indian connections. Among them are Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire, the seat of the Curzons; and Powis castle in Wales, which is linked to Clive of India.

At Eastern Eye’s Arts Culture and Theatre Awards (ACTAs) earlier this year, the National Trust won the community engagement award “for shining a light into hidden corners of the British Empire”. It did so despite being attacked by right-wing politicians and commentators.