CAMBRIDGE University has set up the first ever fellowship to conduct research on indentured Indians, who were shipped out to the Caribbean, Fiji, South Africa and many other places to work on plantations in harsh conditions.

But the tale of forgotten indentured Indians, a third of whom were lone women, often widows or abandoned wives, can be told in very human terms.

For example, a 27-year-old woman called Sujaria arrived in British Guiana on board The Clyde on November 4, 1903. She was travelling alone and was also four months pregnant.

Her great granddaughter, Gaiutra Bahadur, now an associate professor in the department of arts, culture and media at Rutgers University in Newark in America, has tried to find out as much as possible about Sujaria to tell a much wider story.

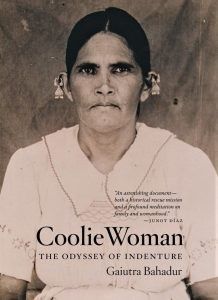

She has written a book, called Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture, which Cambridge praised as “a major study of the lives of Indian women who became indentured labourers to colonial plantations in the nineteenth century”.

Bahadur, who has recently been based at Selwyn College, Cambridge, as a visiting fellow, said: “My great-grandmother Sujaria didn’t leave behind letters or diaries describing the circumstances that led her to climb aboard a ship bound for the other side. Coolie Woman is not only a family history, but a broader social and narrative history of indenture; the system that, for roughly 80 years after the abolition of slavery in the British empire, provided exploitable bonded labour to plantation owners across the globe.”

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies, which resides on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966, it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The name “Guyana” derives from Guiana, an earlier name for a larger region that included the areas now called Guyana (British Guiana), Suriname (Dutch Guiana), French Guiana, the Guyana Region in Venezuela (Spanish Guyana), and Amapá in Brazil (Portuguese Guiana).

Selwyn College and the Ameena Ghafoor Institute, founded by Ameena Ghafoor, 82, a leading philanthropist and businesswoman in Guyana, “collaborated closely in setting up the programme which allows a scholar to spend eight weeks at the university, conducting research”.

The programme will run initially for five years, but Cambridge hopes that with adequate funding, a permanent professorship can be set up.

The study of indentureship was one of the recommendations made in the report of the Legacies of Enslavement at Cambridge Advisory Group.

Selwyn College appointed Bahadur as the Ramesh and Leela Narain visiting bye-fellow in Indentureship Studies. It was funded by Guyana-born Niven Narain, “a recognised pioneer in technology development at the intersection of biology and AI” in honour of his parents, Ramesh and Leela Narain.

“Bye fellow” describes “a Fellow who is not ‘on the foundation’ of a College, who may or may not have fewer privileges than a full fellow, but who takes no part in the government of the College”. He or she is usually temporary.

Bahadur explained her work in Cambridge: “Since mid-June, I’ve been doing archival research at Cambridge on the decolonisation of Guyana. The working conditions on the sugar plantations in the post-slavery and the post-independence period gave rise to a multiracial, anti-colonial political party that was also Marxist. My research has helped me document the consequences of British and US intervention in the colony’s affairs to manoeuvre the party and its leaders, Cheddi and Janet Jagan, out of power. An AngloAmerican policy of ‘divide and decolonise’ has had tragic consequences for Guyana’s political history.”

Bahadur was born in Guyana in 1975 and moved to the US with her family when she was six.

Her appointment was recommended by David Dabydeen, 67, an honorary fellow at Selwyn. He, too, was born in Guyana, came to Britain at 14, read English when he was an undergraduate at Selwyn and is now a novelist, poet, diplomat and academic. He is also a director of the Ameena Gafoor Institute.

Asked about his own family history, Dabydeen confessed: “I have no idea whatsoever, and most Guyanese have no idea, whatsoever. Even what part of India they’re from, whether it’s Bihar or UP (Uttar Pradesh).”

He thinks an ancestor – “my great, great, great, great grandfather” – got on to a boat in Calcutta in 1855. Calcutta, an important port during the days of British rule, was where labourers scooped up or even kidnapped from Bihar or Uttar Pradesh, set sail for faraway places, usually never to return.

Dabydeen has been to India many times without being able to solve the mystery of his origins.

As to the definition of indentured labour, he said: “Indenture is basically a contract, usually five years, which binds you to a particular plantation. To begin with, you were offered a return passage to India. But then that was terminated. And you were offered land instead, if you stayed on after five years.

“So a lot of people stayed on. Because if you were really, really, really poor in India – and most of the indentured labourers were dalits or chamars or people from the lowest caste – they had no chance or a very, very slim chance of owning land in India. Whereas in Guyana, it was a huge boon for the indentured labourers to be able to own land.”

Dabydeen added: “There’s no course, no fellowship, no lectureship, no professorship anywhere in the world dedicated to indentureship. So basically, that’s our work at Cambridge, to create a subject, to give it high credibility, because obviously, Cambridge University is one of the top universities in the world, and to move the subject from the margins to the centre.

“If we have a permanent professorship, named after a philanthropist, if we have something permanent in the history department, then courses can be offered for undergraduates. Graduates can be encouraged to do PhDs and MAs. It’s very important that we have a permanent post and actually what we were looking for is a philanthropist who wants his or her name permanently inscribed in the history of Cambridge University. A permanent posts costs £2 million.

“I just think the time is right now for indentureship studies to be entrenched in British academia. We’ve invested heavily in the study of slavery in many, many universities in Britain, so post-slavery is a very important subject.”

The numbers involved are staggering. Dabydeen revealed: “Between 1838 and 1920, 2.1 million Indians left for the Caribbean, for Mauritius, for Fiji, South Africa, Guyana and Trinidad. But then the French also shipped maybe another million to Réunion Island, Martinique, to Guadeloupe, to French Guiana. And, of course, the Dutch also shipped out Indians to Suriname, Curaçao and the other Dutch West Indian islands.

“And then the second wave of migration was about 15-20 million people crossing the Indian Ocean to work in Malaysia, South Africa, Fiji, Uganda, Kenya, wherever the indentured had settled. So you’re talking about the largest migration of people in the 19th century. Given that mass movement out of India, it’s surprising that the focus has remained completely on slavery, as opposed to what happened afterwards. What was the legacy of slavery? The legacy of slavery was, obviously, indentureship.”