It will be ten years next week since the murder of Fusilier Lee Rigby.

There were so many shocking, frightening aspects of this brutal killing. It was the vicious murder of a soldier in broad daylight of a Wednesday afternoon. In contrast to the coordinated plots of 9/11 and 7/7, the killing was a much simpler form of DIY terrorism. After hanging around the Woolwich barracks, looking for a soldier to attack, Lee Rigby’s killers knocked him over with a car, before killing and mutilating him with a set of kitchen knives, purchased the previous day at Argos.

Chillingly, his killers made no attempt to escape, instead accosting passers-by to video on mobile phones their blood-soaked message about their motives for the attack. “I want a war in London,” one of the perpetrators told a French-British teacher, much praised for her calm intervention in the ten minutes before the police arrived. One small mercy that an attempt to decapitate the dead soldier was botched, as was the killer’s intention to be killed by the police, who shot and arrested the killers, now serving life sentences.

“I remember being very frightened by all of this ‘war talk’. He had killed a soldier. Does all of this talk of war put an idea into people’s minds?” Julie Siddiqi – working for the Islamic Society of Britain at the time – told me. A decade on, she still vividly recalls hearing the news break on the car radio during the school run before seeing the shocking scenes on TV. “I responded to it first at a human level, ” she says, as a parent, seeing the picture of this young man in a uniform. She also felt viscerally how fraught this moment would prove for community relations. “As a Muslim woman wearing a headscarf, you are never quite sure how people may respond to you. That was genuinely scary too,” Siddiqi told me.

Rival extremists were certainly keen to accept and to reciprocate the offer of ethnic and religious conflict. The BNP leadership declared that the killing “signalled the beginning of the civil war,” and the EDL marched on Woolwich and threw missiles at the police. The media granted an extraordinary level of media profile to Anjem Choudary, the leader of the banned al-Mujaroun group, a close associate of the perpetrators. “What he said explains what he did,” he told Newsnight, claiming that “Not many Muslims would disagree with it.” British Muslims at the time were “sick and tired of nobody getting much opportunity to speak except for him,” Siddiqi told me.

If extremists of all stripes knew what they wanted to happen next, others felt uncertain about how to respond. Mainstream Muslim groups were vocal in their condemnation of the murder but wary of being too much in the spotlight. “People could struggle to find a language to own the moment without being to blame for it,” Siddiqi told me. “But if you speak up, with compassion, and showing your shock and horror, you are not labelling Islam, but being part of a conversation with people from all backgrounds. I strongly felt we needed to offer empathy and compassion rather than the main instinct being to not say anything that might draw attention to ourselves.” Simple symbolic acts – tea at the mosque, laying flowers together at the barracks – sought to provide solidarity and reassurance.

The Rigby family, in their grief, proved consistently strong voices in opposing those who sought to use Lee’s name to stir up hatred or division, in the immediate aftermath and much later. In 2020, they found it “heartbreaking and distressing” that some tried to exploit his name and image to attack the Black Lives Matter anti-racism protests, since he had “proudly served his country to protect the rights and freedoms of all”.

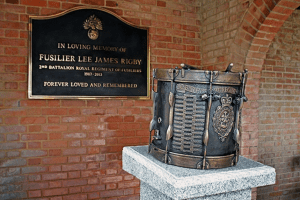

Yet how to commemorate Lee Rigby’s service and sacrifice became a contested issue. A powerful memorial of a bronze drum and plaque was unveiled in the soldier’s hometown of Middleton in 2015. Rigby’s name was commemorated on a plaque at St George’s Garrison Church, opposite the barracks, alongside others who had fallen in service.

There were unofficial tributes where he fell but also banners and flags left by extreme groups, to the family’s distress. But removing unsuitable tributes without providing a suitable one too caused frustration among those without extreme views. An unofficial memorial paving stone appeared, and was removed. A memorial tree was finally planted in Lee Rigby’s memory, on the spot where he was killed, along with a plaque, recommending charities to support in his name. Finding this suitable resolution should not have taken six years.

There will be church services in Woolwich and Lancashire, a commemorative football match in Bury. “What tears me apart is to think that people have forgotten him 10 years on,” his mother told newspapers recently, describing her enduring grief. The tenth anniversary is a chance to show that he must not be. Let Lee Rigby’s name and service be honoured and remembered – and those of his killers forgotten.